According to Kevin Cashman in Forbes magazine, coaching and developing others are among the top three most important leadership competencies. Yet, despite such a high rating of importance, coaching scores as the lowest practiced competency around the world.i Leaders today have a real interest in learning skills that benefit their organizations, especially in the constantly changing world in which they operate. The courts are no exception.

Time and again when interviewing court leaders around the country, the same pain points come up:

- Low employee retention, especially of younger workers

- Lack of engagement

- Resistance to change

- Poor teamwork

While several factors contribute to these problems, like low pay and difficult clients, research also shows that employees who feel empowered, respected and like they’re making a difference are more likely to stay onboard. In addition, effective managers who are good communicators can boost a company’s retention — and its bottom line.ii

One way to solve these problems is to develop a culture of coaching, that is, a coach approach to leadership. When leaders learn and practice coaching skills with their direct reports, their working relationships are improved, job satisfaction and productivity go up, conflicts are reduced, employees feel empowered and more loyal to the organization. In other words, the pain points mentioned above are reduced, and courts, as well as the public, benefit.

In this article, coaching is defined, leadership trends explored, the relationship between coaching and productivity explained, and the application to court leaders, including judges, spelled out.

What is coaching?

The International Coaching Federation (ICF) defines coaching as partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential.iii Coaching creates a dialogue between a coach and coachee that moves a conversation forward and towards goals the coachee is seeking to attain. Unlike mentoring, which draws upon the experience of the mentor, coaching encourages the coachee to find their own solutions to the problems they face. Unlike training, which follows a plan that leads the student to a set learning objective, in coaching, the coachee decides the direction they wish to take and the objectives they wish to achieve. Unlike therapy, which helps the client come to terms with their past, coaching is forward thinking.

Many kinds of coaching and coaches exist, in fact the world of coaching has proliferated over the last two decades. Executive coaching, wellness coaching, personal coaching, performance coaching and many more categories exist. This article discusses how performance coaching impacts organizations like the courts. Performance Coaching is a process where one person (supervisor, manager, leader) facilitates the development and action planning of another (employee, direct report), in order that the individual can bring about changes in their lives and work.

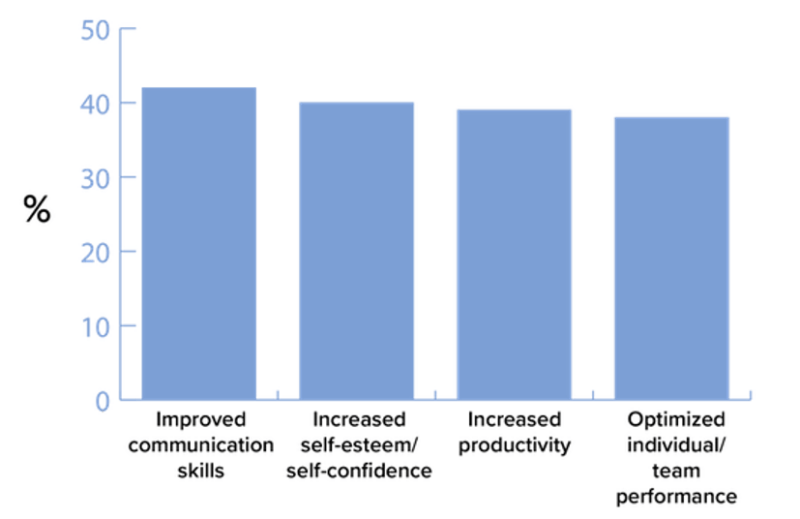

The research shows that coaching can have a very positive effect on employee performance. Individuals who partner with coaches have reported several benefits, including those in the chart below.iv

All coaches, including leaders who coach their employees, are trained to have a particular mindset: they exhibit a coach approach to leadership. This mindset can be summarized as follows:

- Coaches don’t talk, they listen.

- Coaches don’t give information, they ask questions.

- Coaches don’t offer ideas, they generate ideas from employees.

- Coaches don’t share their story, they tap into the employee’s experience.

- Coaches don’t present solutions, they expand the employee’s thinking.

- Coaches don’t give recommendations, they empower employees to choose.v

Most leaders say they know how to coach their employees, yet when asked to demonstrate coaching, they instead demonstrated a form of consulting, essentially giving advice or making suggestions such as “First you do this” or “Why don’t you…” or “This worked for me…”. For many, coaching skills are a new skill to learn, a new tool for their leadership toolbox. Leaders do not need to be certified coaches to successfully coach their employees to higher performance and engagement. They need to invest in learning coaching skills and then hone these skills over time. Even a short training targeted at essential skills, along with a safe environment to practice in, leads to a marked improvement in coaching skills.vi

Leadership trends

In addition to understanding what coaching is and that learning and practicing skills is important, leaders watch trends before they commit valuable resources to training.

Here are what some of the experts are seeing as trends in leadership.

- Need for agility. Leaders and their organizations are becoming / must become more agile to survive and thrive. As leaders, it’s important to adopt a nimble mindset and culture.

- Evolving leadership norms. The age range in the workforce will continue to expand. With the decrease of age-based seniority, leadership will be taken by the best person for the role and will likely shift frequently in an agile environment.

- Foster and sustain employee engagement. Leaders and organizations need to focus on soft skills such as emotional intelligence that have a strong impact on engagement and the effort employees put into communicating.

- Taking a holistic approach to human capital development. Helping employees thrive in all areas of their lives (not just work), will create more engagement, productivity and overall happier employees.

- Leadership empathy. Gen Y and Gen Z talent will continue to leave command-and-control cultures for collaborative workplaces. The ability to understand, relate to and be sensitive to employees, colleagues and communities will be paramount. We will see an even greater emphasis on listening, relating and coaching to drive effective leadership.

- A focus on individual growth. Leaders need to identify and build talent quickly. Helping employees reach their peak potential will be required to help the organization stay competitive and thrive.vii

These trends influence industry and business, as well as courts and other government agencies. Coaching is taking off because it is helping individuals and organizations not only adapt to change but thrive, and it fits well with the trends outlined above. Courts must change and adapt, or the problems cited in the first paragraph of this article will tear at their very fabric. As one court administrator in Arizona said about the bleeding of younger employees to other industries, “If we don’t change what we are doing, when we retire, no one will be left to run the courts.” As court leaders know, losing an employee costs up to one-and-one-half to two times that employee’s salary. The costs include recruitment, onboarding, training, ramp time to peak performance, loss of engagement of others due to high turnover, higher error rates, and general culture impacts. Several critical areas have a large effect on employee retention, and coaching is by its nature a means to remedy them: Employee engagement (or disengagement), adaptability to change, team building and burnout.

Employee engagement

A Gallup report called “The State of the American Workplace,” published in 2017 estimates that 67% of employees in U.S. companies are disengaged. Of that 67%, 16% are actively disengaged. Disengagement leads to employee turnover, conflict in the workplace, high rates of absenteeism, workers just hanging on until they can retire, and the like. Actively disengaged employees can even sabotage a workplace. On the other hand, highly engaged workplaces are:

- 50% more likely to have lower turnover

- 56% more likely to have higher-than-average customer loyalty (think public trust and confidence)

- 38% more likely to have above average productivity

- 27% more likely to report higher profitability (think more efficient case management)viii

A coach approach to leadership fosters engagement of employees because it facilitates clear communication about expectations:

- Coaching uncovers blocks to resources

- Dialogues shift from what must be done to what can be done

- Authentic acknowledgement takes place

- The focus is on the person, not just the result

- Shifts in awareness result in sustainable behavioral and developmental change

- Coaching gives space for opinions and ideas

- Coaching connects personal goals and organizational goals

Change management

Another area of serious need as cited by the educators and court administrators interviewed by the author is change management. Courts are places of continuous change, as well as places loyal to precedent and tradition. Change is constant, yet change can cause some of the highest areas of friction or conflict in an organization. People fear change, and coaching can help work through the fear and resistance commonly seen when change is forecast or implemented. Coaching

- Provides a platform to discuss resistance, fear and confusion

- Helps teams and individuals understand the connection between the coming change and their goals

- Allows for discussion about possibilities

- Addresses resource needs

- Addresses obstacles

A coach approach supports employees to move farther, faster, easier, quicker than they would have without a coach. Coaching becomes a “safe container” to discuss and address the INTERNAL fears and resistance individuals have that often affect EXTERNAL behaviors during times of change.

Teamwork

Another area of challenge often cited by court administrators was poor teamwork. Research shows that when coaching is embedded in the culture of an organization, average or even dysfunctional teams begin to turn around and become high performing teams. This happens because coaching

- Models a new, more productive, way of communication

- Promotes trust

- Embeds accountability

- Clears pathways to clarity and focus on common goals and results

- Models acceptance of other’s ideas, opinions and ways of being, even when there isn’t agreement.

Burnout

Finally, when it comes to employee burnout, how can a coach approach to leadership help? In a recent article in the Harvard Business Review, foremost expert on burnout, Christina Maslach, points out that burnout is a company problem, not an employee problem. In other words, a company’s culture and leadership create the environment that burns people out. She describes employee motivators as challenging work; recognition of one’s achievements; responsibility; the opportunity to do something meaningful; involvement in decision making; and a sense of importance to the organization. Leaders, Maslach states, could save themselves a huge amount of employee stress and subsequent burnout, if they were just better at asking people what they need.ix Coaching skills provide the means to ask.

Judges and coaching skills

How can judges use coaching skills? For presiding judges, who are court leaders, the answer is that they can use them in the same way as their court administrator. For other judges, coaching has wide applicability for judges working in family court, where self-represented litigants have become the rule. Since coaching questions are designed to help people arrive at what they need and want, rather than tell them what to do, they are perfect questions for judges to ask self-represented litigants. Coaching questions by design avoid putting people on the defensive. In specialty courts, where judges often interact directly with defendants, the same applies. Using a coach approach helps people in front of the court figure out what they need for themselves and from the courts, while avoiding telling people how to proceed.

In conclusion, a coach approach to leadership involves learning and practicing a specific set of skills designed to bring out the best in people. In the administration of justice, employees of the courts are critical to the courts’ success. Court leaders, from the line supervisor to the presiding judge, can learn and use coaching skills to keep these critical people on board, as well as increasing their engagement, teamwork and adaptability to change. Court leaders don’t need to become certified coaches, rather, they can learn coaching skills and adopt a coach approach to leadership. They will benefit themselves, their employees and their courts in the process.

NOTES

i Cashman, Kevin. “Five Coaching Practices to accelerate the growth of others.” Forbes, January 29, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevincashman/2018/01/29/five-coaching-practices-to-accelerate-the-growth-of-others/#5fe5daa05388

ii Cheng, Candace. “3 Factors Strongly Linked to Better Employee Retention, According to 32 Million LinkedIn Profiles.” November 20, 2019. https://business.linkedin.com/talent-solutions/blog/trends-and-research/2019/3-factors-linked-to-better-employee-retention

iii International Coaching Federation. Accessed January 15, 2020. http://becomea.coach/?navItemNumber=4090

iv 2017 ICF Global Consumer Awareness Study. https://coachfederation.org/research/consumer-awareness-study

v Webb, Keith. “What it Really Means to be a Coach.” Accessed at https://keithwebb.com/what-really-means-to-be-coach/, January, 2020.

vi Milner, Julia and Trenton Milner. “Most Managers Don’t Know How to Coach but They can Learn,” HBR, August 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/08/most-managers-dont-know-how-to-coach-people-but-they-can-learn

vii “Leadership Trends To Watch For From Now To 2022,” accessed at https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2018/08/21/leadership-trends-to-watch-for-from-now-to-2022/#70df3c936658 and “14 Leadership Trends That Will Shape Organizations In 2018,” accessed at https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2018/01/30/14-leadership-trends-that-will-shape-organizations-in-2018/#50ce4fe15307 from https://www.coachingoutofthebox.com/coaching-resources/blog .

viii Gallup, State of the American Workplace, 2017. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/238085/state-american-workplace-report-2017.aspx

ix Harvard Business Review, “Burnout Is About Your Workplace, Not Your People,” 2019. https://hbr.org/2019/12/burnout-is-about-your-workplace-not-your-people

Nancy Fahey Smith is a coach, teacher, trainer and facilitator with over 10 years of experience working in court training and education, first at the Washington State AOC and then at Arizona Superior Court in Pima County (Tucson, AZ). She is co-owner of Sustainable Change Coaching and Consulting. Nancy branched out into this new business where she and her partner, Leslie Gross, teach court and non-profit leaders coaching skills to improve employee performance, satisfaction, retention, and adaptability to change. She is passionate about helping court leaders create a culture of coaching in their organizations through a coach approach to leadership. She came to the courts with 16 years of experience in education, both as a community college instructor and a high school teacher in Tucson, and as a curriculum coordinator at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA. Nancy taught many kinds of court related classes while at the courts, and has a special interest in adult learning theory and application. She speaks periodically at conferences on topics related to judicial education and publishes articles for the National Association of State Judicial Educators (NASJE). Currently, she serves on the NASJE the Communication Committee. She earned her bachelor’s degree in French and History at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and her Master’s in French from the Free University of Brussels, Belgium. Nancy grew up in a Navy family, married into an Army family and served four years as an Army Intelligence officer. She has traveled widely around the United States and Europe as well as to Peru, Mexico and China. She likes the outdoors, and swims, hikes, bikes and does yoga for fun and fitness. She can be reached at nancy@sustainablechangecoaching.com.

Like a mechanical timepiece, judicial branch education (JBE) programs have many moving parts. For a JBE program to be effective, these moving parts must complement one another and move together: facilities must nurture a learning environment, content must meet participant professional needs, materials must be clear and engaging, faculty must be prepared, and participants must show up at the right place at the right time, ready to learn. As the Globe Theater manager was fond of reminding young Shakespeare during moments of trepidation in the film Shakespeare in Love, “it always comes together in the end.” Indeed it does, but never without the effort of a team.

Like a mechanical timepiece, judicial branch education (JBE) programs have many moving parts. For a JBE program to be effective, these moving parts must complement one another and move together: facilities must nurture a learning environment, content must meet participant professional needs, materials must be clear and engaging, faculty must be prepared, and participants must show up at the right place at the right time, ready to learn. As the Globe Theater manager was fond of reminding young Shakespeare during moments of trepidation in the film Shakespeare in Love, “it always comes together in the end.” Indeed it does, but never without the effort of a team. Dr. Deborah Williamson is a veteran manager with the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts, Dr. Deborah Williamson currently serves as the Executive Officer of the Department of Court Services. Spanning over two decades, Williamson’s career with the state court system has involved diverse assignments such as management of the statewide juvenile intake program, grants office, and the nationally renowned judicial branch education program. A Doctor of Philosophy graduate from the University of Kentucky, Dr. Williamson is currently developing courses in the subfield of criminology for undergraduates majoring in sociology. Her publications have appeared in Crime and Delinquency, Journal of Social Work in Education, and Juvenile and Family Court Journal.

Dr. Deborah Williamson is a veteran manager with the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts, Dr. Deborah Williamson currently serves as the Executive Officer of the Department of Court Services. Spanning over two decades, Williamson’s career with the state court system has involved diverse assignments such as management of the statewide juvenile intake program, grants office, and the nationally renowned judicial branch education program. A Doctor of Philosophy graduate from the University of Kentucky, Dr. Williamson is currently developing courses in the subfield of criminology for undergraduates majoring in sociology. Her publications have appeared in Crime and Delinquency, Journal of Social Work in Education, and Juvenile and Family Court Journal. Adam K. Matz, M.S. is a Research Associate with the American Probation and Parole Association (APPA) and former Statistician for the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts. His research has focused on topics of gang violence, cultural congruence in local circuit courts, social efficacy in local communities, as well as job satisfaction and organizational climate within juvenile justice institutions. Additionally, he now serves as consultant and Business Analyst for the Kentucky Court of Justice data system improvement project. Mr. Matz earned his bachelor’s degree in police studies and master’s degree in correctional and juvenile justice studies from Eastern Kentucky University. His publications have appeared in journals such as Criminal Justice and Behavior and Criminal Justice Review.

Adam K. Matz, M.S. is a Research Associate with the American Probation and Parole Association (APPA) and former Statistician for the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts. His research has focused on topics of gang violence, cultural congruence in local circuit courts, social efficacy in local communities, as well as job satisfaction and organizational climate within juvenile justice institutions. Additionally, he now serves as consultant and Business Analyst for the Kentucky Court of Justice data system improvement project. Mr. Matz earned his bachelor’s degree in police studies and master’s degree in correctional and juvenile justice studies from Eastern Kentucky University. His publications have appeared in journals such as Criminal Justice and Behavior and Criminal Justice Review. James R. Columbia retired from the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts in 2009 after a 22-year career that included positions as a Court Designated Worker, Regional Supervisor and Information Systems Supervisor for the Juvenile Services division, in which capacity he coordinated development of a statewide, electronic case management and data system. He subsequently was appointed Manager of the Records and Research & Statistics divisions of the AOC. He now serves as consultant and Business Analyst for the Kentucky Court of Justice data system improvement project. Mr. Columbia holds an associate degree in science from Maysville Community College and a bachelor’s degree in business, with a major in accounting, from the University of Kentucky.

James R. Columbia retired from the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts in 2009 after a 22-year career that included positions as a Court Designated Worker, Regional Supervisor and Information Systems Supervisor for the Juvenile Services division, in which capacity he coordinated development of a statewide, electronic case management and data system. He subsequently was appointed Manager of the Records and Research & Statistics divisions of the AOC. He now serves as consultant and Business Analyst for the Kentucky Court of Justice data system improvement project. Mr. Columbia holds an associate degree in science from Maysville Community College and a bachelor’s degree in business, with a major in accounting, from the University of Kentucky. Janet Bixler has joined the Administrative Office of the Courts as a Business Analyst for researching the needs for a unified case management system. She has served as a business analyst, technical writer, and project manager in the technology industry. Ms Bixler has expertise in researching current information technology processes, developing new processes, and documenting and training those processes to applicable users. Ms. Bixler earned her bachelor’s degree in journalism with a minor in political science from the University of Kentucky. She has completed information technology classes at the Kentucky Community & Technical College System.

Janet Bixler has joined the Administrative Office of the Courts as a Business Analyst for researching the needs for a unified case management system. She has served as a business analyst, technical writer, and project manager in the technology industry. Ms Bixler has expertise in researching current information technology processes, developing new processes, and documenting and training those processes to applicable users. Ms. Bixler earned her bachelor’s degree in journalism with a minor in political science from the University of Kentucky. She has completed information technology classes at the Kentucky Community & Technical College System. Jean Conn serves as a Business Analyst for the Administrative Office of the Courts. She will work with a newly appointed project team to research and document the business needs for a new case management system. Mrs. Conn was a Project Manager and Business Analyst for Humana, Automatic Data Processing, Kindred Healthcare and Brown & Williamson Tobacco. She has extensive experience working as a liaison between Information Technology and the business users. Mrs. Conn has implemented a variety of systems such as HRIS, benefits enrollment, medical insurance, and clinical systems. She graduated from Sullivan Junior College majoring in computer programming. She also attended Sullivan University and Bellarmine University.

Jean Conn serves as a Business Analyst for the Administrative Office of the Courts. She will work with a newly appointed project team to research and document the business needs for a new case management system. Mrs. Conn was a Project Manager and Business Analyst for Humana, Automatic Data Processing, Kindred Healthcare and Brown & Williamson Tobacco. She has extensive experience working as a liaison between Information Technology and the business users. Mrs. Conn has implemented a variety of systems such as HRIS, benefits enrollment, medical insurance, and clinical systems. She graduated from Sullivan Junior College majoring in computer programming. She also attended Sullivan University and Bellarmine University.

Janet Bixler has joined the Administrative Office of the Courts as a Business Analyst for researching the needs for a unified case management system. She has served as a business analyst, technical writer, and project manager in the technology industry. Ms Bixler has expertise in researching current information technology processes, developing new processes, and documenting and training those processes to applicable users. Ms. Bixler earned her bachelor’s degree in journalism with a minor in political science from the University of Kentucky. She has completed information technology classes at the Kentucky Community & Technical College System.

Janet Bixler has joined the Administrative Office of the Courts as a Business Analyst for researching the needs for a unified case management system. She has served as a business analyst, technical writer, and project manager in the technology industry. Ms Bixler has expertise in researching current information technology processes, developing new processes, and documenting and training those processes to applicable users. Ms. Bixler earned her bachelor’s degree in journalism with a minor in political science from the University of Kentucky. She has completed information technology classes at the Kentucky Community & Technical College System. Adam K. Matz, M.S. is a Research Associate with the American Probation and Parole Association (APPA) and former Statistician for the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts. His research has focused on topics of gang violence, cultural congruence in local circuit courts, social efficacy in local communities, as well as job satisfaction and organizational climate within juvenile justice institutions. Additionally, he now serves as consultant and Business Analyst for the Kentucky Court of Justice data system improvement project. Mr. Matz earned his bachelor’s degree in police studies and master’s degree in correctional and juvenile justice studies from Eastern Kentucky University. His publications have appeared in journals such as Criminal Justice and Behavior and Criminal Justice Review.

Adam K. Matz, M.S. is a Research Associate with the American Probation and Parole Association (APPA) and former Statistician for the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts. His research has focused on topics of gang violence, cultural congruence in local circuit courts, social efficacy in local communities, as well as job satisfaction and organizational climate within juvenile justice institutions. Additionally, he now serves as consultant and Business Analyst for the Kentucky Court of Justice data system improvement project. Mr. Matz earned his bachelor’s degree in police studies and master’s degree in correctional and juvenile justice studies from Eastern Kentucky University. His publications have appeared in journals such as Criminal Justice and Behavior and Criminal Justice Review. James R. Columbia retired from the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts in 2009 after a 22-year career that included positions as a Court Designated Worker, Regional Supervisor and Information Systems Supervisor for the Juvenile Services division, in which capacity he coordinated development of a statewide, electronic case management and data system. He subsequently was appointed Manager of the Records and Research & Statistics divisions of the AOC. He now serves as consultant and Business Analyst for the Kentucky Court of Justice data system improvement project. Mr. Columbia holds an associate degree in science from Maysville Community College and a bachelor’s degree in business, with a major in accounting, from the University of Kentucky.

James R. Columbia retired from the Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts in 2009 after a 22-year career that included positions as a Court Designated Worker, Regional Supervisor and Information Systems Supervisor for the Juvenile Services division, in which capacity he coordinated development of a statewide, electronic case management and data system. He subsequently was appointed Manager of the Records and Research & Statistics divisions of the AOC. He now serves as consultant and Business Analyst for the Kentucky Court of Justice data system improvement project. Mr. Columbia holds an associate degree in science from Maysville Community College and a bachelor’s degree in business, with a major in accounting, from the University of Kentucky.