by Anthony P. Wartnik, Judge (Retired)

There are people in your courts who deserve special attention. Some have committed crimes they didn’t understand and some have been convicted of crimes for which they are not fully culpable and both are doomed to getting caught in the juvenile and or adult criminal justice revolving door unless we recommend and or do things differently. They may have Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) and need special attention and special approaches to sentencing in order to avoid being continually caught in the revolving door. This paper identifies and discusses ten principles for the sentencing of people with FASD. These ten principles of sentencing for people with FASD were developed through the joint effort of Dr. Ann Streissguth, recently retired as the Director of the Fetal Alcohol Drug Unit (FADU) of the University of Washington School of Medicine, Ms. Kay Kelly, Project Manager of the FASD Legal Issues Resource Center at FADU, Professor Eric Schnapper, University of Washington School of Law liaison to the FADU, and myself.

The ten principles for sentencing people with FASD were part of the Power Point presentation delivered by this author at the 2nd International Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Conference on March 10, 2007. The discussion that follows each principle is based on my experiences in dealing with juveniles and adults with FASD or suspected of having FASD during my nearly twenty-five year career as a judge of the King County Superior Court in Seattle Washington, and particularly from 1994 until my retirement in 2005. My reference point throughout the discussion that follows is the sentencing laws of the State of Washington for felonies, frequently referred to as the Sentencing Reform Act or SRA. I will, however, cite a limited amount of case law from other jurisdictions to support a basic legal principle that FASD can constitute mitigation in sentencing. It should be noted that the SRA is a system for determining the presumed sentencing range for each offender based on the seriousness of the crime for which he or she is being sentenced and that person’s prior felony criminal history. The sentencing judge is required to impose a sentence that is within the standard range unless there are substantial and compelling reasons to impose an exceptional sentence outside the range, either below or above it. The judge has much more discretion in sentencing for misdemeanor and gross misdemeanor criminal offenses since the SRA does not apply to this class of crimes.

The fact that a person has FASD may bear on sentencing in one or more of three ways. (1) The presence of FASD may reduce culpability for the criminal conduct. (2) The presence of FASD may require different measures to reduce the chances of recidivism. (3) The presence of FASD usually means significant difficulties functioning in adult society, problems which a particular sentence may either aggravate or alleviate.

The first principle for sentencing of people with FASD is to consider whether the disability entails reduced culpability and thus warrants a less severe sentence. Assuming that there is statutory authority for the exercise of discretion or for sentencing outside a standard sentencing range, look at and consider matters that constitute mitigation. In Washington, our statute permits an exceptional (lower) sentence where the defendant’s capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of his or her conduct, or to conform conduct to the requirements of the law, was significantly impaired. Either or both of these factors may be present when an offender has FASD. There is case law authority supporting the concept that FASD can constitute a basis for a finding of mitigation for sentencing purposes. See, Silva v. Woodford, 279 F.3rd 825 (9th Cir. 2002). See, also, State v. Brett, 126 Wn2d 868 (2001). Both of these cases dealt with ineffective assistance of counsel for not investigating or seeking a diagnosis of FASD for sentencing mitigation. See, also, the case of Castro v. Oklahoma, 71 F3rd 1502 (1995), which held that a criminal defendant was entitled to appointment of an expert to develop evidence regarding FASD provided that there was a substantial showing that his mental state was in dispute and was relevant to the outcome of the case, to either the guilt determination or to the sentence to be imposed.

It must be kept in mind that individuals with FASD frequently do not fully grasp the standards of conduct reflected in the criminal law. For example, an individual with FASD would usually understand that it was wrong to steal from a store, but might not understand that it was wrong to temporarily take an acquaintance’s car without permission. Second, individuals with FASD at times engage in impulsive behavior, unable to resist the urge to do something they may grasp as wrong. Shoplifting items for personal use or for the use of a “friend” is among the offenses they commit most often. The lack of apparent predisposition to commit a crime, the participation by being induced by others, is also a mitigating circumstance in Washington. Individuals with FASD, often anxious to please others and unsophisticated about whether they are being used, can too easily be persuaded to engage in conduct, which they may or may not fully realize is criminal, by individuals with substantial criminal records and or substantial criminal sophistication.

The second principle for sentencing is to avoid lengthy (or any) incarceration in favor of longer periods of supervision. Although community safety is of primary or significant concern in any sentencing, do not let it inappropriately control your better judgment. When you are uncomfortable due to concerns about whether leaving a defendant with FASD in the community presents a risk to the community, it is far too easy to use community safety considerations as a justification for incarceration rather than facing the issue head-on in relation to long-term consideration of what the risk to the community will be upon release of the defendant from incarceration. Lengthy incarceration usually does not contribute in any way to preventing further offenses by individuals with FASD; often times it may do the opposite. Remember that this offender normally doesn’t learn from prior experiences and is not able to apply them to new situations. The result may be that you are able to protect the community during the period of incarceration but the offender will be as or more dangerous upon release from custody due to an inability to learn from the incarceration experience and an inability to link the incarceration with the crime that gave rise to it.

The prospect of a lengthy sentence (or of a longer sentence for a more serious crime) is unlikely to affect an individual with FASD. These individuals have only a limited grasp of cause and effect and have trouble planning for even a single day; they would usually be incapable of weighing the risk of a long prison term against the hoped for gain from a particular offense. Having served a long sentence may have no effect on future conduct. Individuals with FASD at times do not fully understand why they are (or were) in prison. Conversely, prolonged incarceration may severely harm the ability of an already disabled individual with FASD to function when he or she returns to society. Think of the emotional effect of putting a ten-year-old in an adult prison. Additionally, those disabled by FASD are often vulnerable to victimization, both physically and emotionally, by fellow inmates. An introduction of the defendant with FASD into an inmate population may result in continued destructive influences even after release from custody. The social arrangements that earlier assisted an individual with FASD to function in society (housing, jobs, etc.) are likely to disappear when they are incarcerated for an extended period.

The third principle of sentencing is to use milder but targeted sanctions. Sanctions can work if they are sufficiently limited so as to be non-destructive, are used prospectively and are targeted at affecting very specific conduct. Generalized deterrence is unlikely to be effective because it is directed at a large and complex set of rules (“obey the law or you will go to prison”) which an individual with FASD does not fully understand; in any event, the connection is simply too abstract for an individual with FASD to grasp and understand. People with FASD tend to see things in concrete terms and respond better to concrete presentations. What may work is linking a particular sanction (say, ten hours of community service) to a very specific type of conduct the court wants to prevent (e.g.), getting drunk or shoplifting. These individuals can master the importance and meaning of a particular rule (or a few) tied to known sanctions. The best analogy might be to a rule that a six-year-old would be sent to his room any time he took his sibling’s toys. For such a system to work, the individual with FASD must be repeatedly reminded of the rule (and rule-sanction connection). Repetition is the key to effective learning for those with this disability. And, the sanction should focus on something that is of major significance (e.g.), a sanction for using drugs, but not a sanction for being late to an appointment.

The fourth principle of sentencing is to impose, recommend or arrange for a longer term of supervision. Individuals with FASD have a life-long need for guidance from a non-disabled individual and for a variety of social services. These are not defendants who merely need to (or can) straighten their lives out, or who (as in the case of juvenile offenders) are going to mature with time. Supervision by a Department of Corrections (or other) probation official who understands FASD is of ongoing importance for as long as it can be arranged, both to avoid recidivism and to improve functioning. The court should attempt to impress the importance of this on both the prosecution (which may focus primarily on the amount of prison or jail time) and the defense (which usually seeks to have the defendant on the street and off supervision as soon as possible). The extended supervision sentence is one that, generally, neither side will ask for. It may be necessary to seek legislation that mandates longer periods of supervision for people with FASD just as legislatures have done in other problem areas such as with sex offenders, violent and persistent offenders, etc. Judges should be creative in finding ways to prolong Department of Corrections or other supervision, through the consent of the parties, by postponing final sentencing, or other means.

The fifth principle of sentencing is to use the judge’s position of authority (stature) with the defendant. Individuals with FASD often have great respect for authority figures and are anxious to please. The particular authority and stature of a judge and the trappings of a courtroom (or chambers) can be important tools in shaping their behavior. Where practicable, a defendant with FASD should be asked (over and above any Department of Corrections supervision) to return on a regular basis to report to the judge on how he or she is doing. Positive behavior should be greeted with much praise and support (as we have already learned to do with defendants in the drug treatment court and mental health court settings). Recognition of success (certificates, tokens memorializing periods of sobriety, courtroom applause) may be helpful. This approach has certainly become part of the culture in drug treatment and mental health courts. Failures should be the occasion to review the sentencing plan, call together the interested agencies, implement other services, and discuss with the defendant and the sponsor or advocate the defendant’s plan for improvement.

It may be possible to persuade the defendant, after formal supervision has ended, to continue to come to the courtroom or chambers on a regular basis to report to the judge. While that might have to be voluntary, and most defendants would have no interest, individuals with FASD might be pleased to continue their connection with the judge. I was a local district court judge from 1971 to 1980 where I handled misdemeanor and gross misdemeanor cases. The post-sentence case load was more than the local probation department could supervise effectively. I met anywhere from monthly to every 90 days with many of the people that I had ordered onto probation. This was one of the most enjoyable and satisfying parts of my judicial work. I also believe, based on the responses received from the probationers that they appreciated the personal effort taken by me as “my” judge.

The sixth principle of sentencing is to obtain a sponsor or advocate for the defendant. Individuals with FASD need guidance and assistance from a non-disabled individual. Department of Corrections officials or probation officers will only be available for so long and can devote only a limited amount of time to any one probationer.

Whenever possible, someone else should be found who will agree to help the defendant on an ongoing basis. This might be a family member (such as a responsible parent or sibling), a family friend, a relative, or someone in a local organization (e.g.), a church group, retired citizens group, etc.. Defense counsel or probation officials could be asked to look for someone who would function in this capacity. When found, this individual should be asked to come into court with the defendant to discuss his or her participation. Ideally, such a person would be found before sentencing, and at the hearing, would assure the court and the defendant of his or her willingness to play a supportive role.

The seventh principle of sentencing is to create a structure in the defendant’s life. These individuals often lack the basic skills needed to organize a day. At best, needed tasks (shopping for, and preparing meals, getting to work, laundry, personal hygiene, etc.) may go undone; at worst the individual will drift into destructive conduct for want of any sense of how to better utilize his or her time. Structure could include linkage with vocational rehabilitation services, a sheltered workshop (particularly one that provides job coaches and will help the client find a job that he or she is capable of being successful at and who is also skilled in training the client in maximizing the application of his or her strengths to the requirements of the job). This may include the use of alternative approaches for performing the required work, use of alternative types of tools, equipment, etc. which is a very common practice in training persons with developmental disabilities.

External structure (like an “external brain”) can help greatly. This might include (a) living in a group home or facility with an established regiment (when to get up, eat, etc.), (b) a very structured (even part time) job (indeed one of the values of even part time employment is that it gives someone with FASD something regularized that he or she needs to do every day, (c) a daily schedule created in collaboration with the defendant and overseen by a parent, advocate, sponsor, or other party, (d) involvement in frequently scheduled treatment programs such as classes in anger management , sexual deviancy treatment, drug testing, drug treatment, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings, family counseling, group therapy and recreational groups.

The eighth principle of sentencing is to write out, simplify and repeat rules/conditions of supervision. Individuals with FASD will not readily assimilate rules or admonitions from the court or probation. The steps they are to take need to be put in writing and framed in simple, non-legalistic terminology. The Judgment and Sentence or the Conditions of Supervision Appendix should set out all of the conditions in short and concise statements using simple and understandable (to the defendant) language. Repetition is the key to the manner in which these individuals learn. Once is not enough. Probation officials and, in certain instances the court, need to go over the rules (what to do, what not to do) again and again and again, and in very simple and concise statements. Even requiring the defendant to comply with repetitive tasks is a helpful activity in the learning process (e.g.), require the defendant to call the employer to say, “I am leaving home for work now” and to call the parent or other support person every day to say, “I have finished work and am leaving for home.”

The ninth principle of sentencing is to make sure the probation officer understands FASD. Once sentencing is over, the probation officer ultimately assigned to the defendant will have far more contact with the defendant than will the court. For that reason, the court needs to make sure that the probation officer knows that the defendant has FASD and understands the disability, as well as the communication, expectations, and performance issues and how to address them. The sentencing order should include (in its body or appendix) a statement that the defendant has FASD and an explanation of the disability. Once a probation officer is assigned to the defendant, where possible, that officer should be directed to accompany the defendant to court to discuss his or her case with the judge.

If the defendant is going to be incarcerated, the court should take appropriate steps to assure that prison or jail officials know that the inmate is disabled and that they receive information about the disability.

One of the things you might want to have the probation officer do, or that the court might want to do at the time of sentencing is to give the defendant a card with instructions to keep it on his or her person at all times and to show it immediately to any law enforcement officer who contacts the defendant that says, “I have FASD. I want to talk to an attorney. I want my mother or father/guardian/advocate called immediately and want one of them present before I will talk.”

The tenth and final principle for sentencing of people with FASD is not to overreact to probation violations – particularly status offenses. Those disabled by FASD will often engage in behaviors for which a non-disabled probationer would be punished. Individuals with FASD have difficulty remembering and keeping appointments; whether it is the required meeting with the probation officer or AA attendance, their failure to do so is usually not an act of defiance, but a symptom of the disability. The court could suggest to the probation officer that the problem of missed appointments be dealt with prospectively by setting up a system of prompts and by drawing on the support of the sponsor or advocate.

These individuals may have annoying personal mannerisms that in a non-disabled individual would be a sign of recalcitrance or defiant disrespect. Their characteristic impulsivity can yield inappropriate expressions of anger which in the non-disabled would call for sanctions. However, understanding the nature of the cognitive deficits, probation officials can look past this, evaluating a probationer’s conduct in the context of his or her disability. The focus should be on bringing about compliance with rules of substantial inherent importance (e.g.), not using drugs, rather than rules that the Department of Corrections or probation department would ordinarily enforce in order to encourage the non-disabled probationer to assume responsibility for fulfilling his or her supervision responsibilities.

In conclusion, if individuals with FASD are to be successful on probation or parole, and if they are to take their place in the community as productive and contributing members of society, then all of us who play a role in the system need to provide them with the special attention and special approaches to sentencing and supervision that maximizes their opportunity for success. If we do not address the special needs of those with FASD, and if we do not strive to develop and utilize the special approaches that are unique to their needs, we doom them to a recidivistic life style and continual re-entry into the revolving doors of the justice system, whether it be juvenile court system or the adult criminal justice system.

Anthony P. Wartnik, Judge (Retired)

APW Consultants

8811 SE 55th Pl.

Mercer Island, WA 98040

Phone: 206-232-2970

Cell Phone: 206-290-0451

Email: TheAdjudicator@comcast.net

******

Judge Anthony (Tony) Wartnik (Retired) has a long and distinguished career in law and has been recognized by his peers for his outstanding contribution to his field. His 34 year career as a trial judge started in 1971 as a District Court (Limited Jurisdiction) Judge, and he retired in 2005 as the Senior Judge of the King County Superior Court (General Jurisdiction) of the State of Washington where he served from 1980 to 2005. During his Superior Court career, Judge Wartnik served as Presiding Judge for the Juvenile Court, Chief Judge for the Family Law Court, and chair of the Family Law Department and the Family and Juvenile Law committees. Tony also was the Dean Emeritus of the Washington Judicial College, Chair of the Judicial College Board of Trustees, and Chair of the Washington Supreme Court Education Committee. Judge Wartnik chaired a multi-disciplinary task force to establish protocols for the determination of competency for youth with organic brain damage and chaired Governor Mike Lowry’s Advisory Panel on FAS/FAE.

Judge Wartnik is currently the Legal Director for FASD Experts and a consultant to the University of Washington Medical School’s Fetal Alcohol and Drug Unit (FADU). In his role with FASD Experts, Judge Wartnik provides general legal review of the Team’s functioning and protocol development and also serves as a liaison between the Team and the client’s legal counsel as well as being available as a consultant to legal counsel, providing legal expertise regarding specific issues of relevance. He has been a presenter at numerous local, state, interstate, national and international conferences and workshops on issues related to FASD and the juvenile and adult justice systems. He is a graduate of the SAMSHA sponsored FASD workshop “Training the Trainers.”

Charles Benjamin Schudson, a Wisconsin Reserve Judge Emeritus and long-time NASJE member, served as a state and federal prosecutor, a trial and appellate judge, and as an adjunct professor of law at Marquette University and the University of Wisconsin. For many years, he served on the faculties of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges and the National Judicial College. He has taught at countless judicial colleges and conferences throughout America, and in recent years, served as a Fulbright Fellow teaching at law schools abroad. He also co-authored On Trial / America’s Courts and Their Treatment of Sexually Abused Children (Beacon Press, 1989; 2d ed., 1991).

Charles Benjamin Schudson, a Wisconsin Reserve Judge Emeritus and long-time NASJE member, served as a state and federal prosecutor, a trial and appellate judge, and as an adjunct professor of law at Marquette University and the University of Wisconsin. For many years, he served on the faculties of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges and the National Judicial College. He has taught at countless judicial colleges and conferences throughout America, and in recent years, served as a Fulbright Fellow teaching at law schools abroad. He also co-authored On Trial / America’s Courts and Their Treatment of Sexually Abused Children (Beacon Press, 1989; 2d ed., 1991). A new NCSC report, Elements of Judicial Excellence: A Framework to Support the Professional Development of State Trial Court Judges, is now available. It is a first-of-its-kind resource for judges, mentors, educators, and state court leaders who support and seek to enhance their state systems of judicial professional development.

A new NCSC report, Elements of Judicial Excellence: A Framework to Support the Professional Development of State Trial Court Judges, is now available. It is a first-of-its-kind resource for judges, mentors, educators, and state court leaders who support and seek to enhance their state systems of judicial professional development. Jennifer Wildeman has been with the Arizona Supreme Court’s Education Services Division since 2014. She has worked with Arizona courts since 2007, and has been a NASJE member since 2015. As an Education Projects Specialist, Jennifer works closely with subject matter experts throughout Arizona to help develop timely and relevant trainings for judges and court staff throughout the state. In addition, Jennifer trains court staff on topics ranging from communication to legal authorities.

Jennifer Wildeman has been with the Arizona Supreme Court’s Education Services Division since 2014. She has worked with Arizona courts since 2007, and has been a NASJE member since 2015. As an Education Projects Specialist, Jennifer works closely with subject matter experts throughout Arizona to help develop timely and relevant trainings for judges and court staff throughout the state. In addition, Jennifer trains court staff on topics ranging from communication to legal authorities.

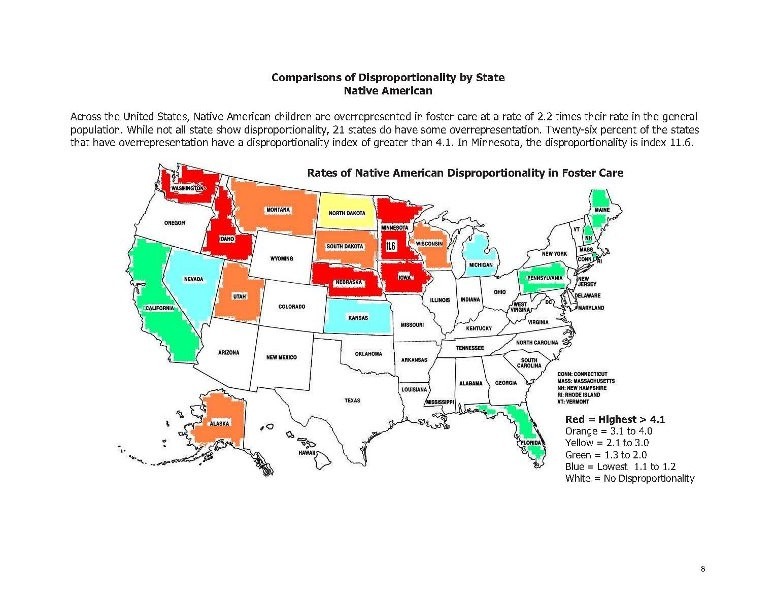

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) Juvenile Justice Model Courts Project, managed by the Juvenile and Family Law Department, has expanded the number of courts participating in the project to 12. Four of the recently added sites in the project (Pittsburgh, Pa., State of Minnesota; New Orleans, La.; and Memphis, Tenn.) are developing goals and addressing challenges to achieve the recommendations from the

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) Juvenile Justice Model Courts Project, managed by the Juvenile and Family Law Department, has expanded the number of courts participating in the project to 12. Four of the recently added sites in the project (Pittsburgh, Pa., State of Minnesota; New Orleans, La.; and Memphis, Tenn.) are developing goals and addressing challenges to achieve the recommendations from the

Gina Jackson, MSW, is a Model Court Liaison for the Victims Act Model Court Project with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges working with several jurisdictions across the country. Ms. Jackson belongs to the Temoke Western Shoshone Tribe. She holds a Masters and Baccalaureate degree in Social Work from the University of Nevada, Reno, with a minor in Early Childhood.

Gina Jackson, MSW, is a Model Court Liaison for the Victims Act Model Court Project with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges working with several jurisdictions across the country. Ms. Jackson belongs to the Temoke Western Shoshone Tribe. She holds a Masters and Baccalaureate degree in Social Work from the University of Nevada, Reno, with a minor in Early Childhood. A Georgia judge recently resigned after that State’s Judicial Qualifications Commission investigated the judge’s Facebook messaging with a defendant appearing in a pending matter before him.

A Georgia judge recently resigned after that State’s Judicial Qualifications Commission investigated the judge’s Facebook messaging with a defendant appearing in a pending matter before him. Justice Crothers regularly conducts training for judges and lawyers on ethics and technology, and on judicial disqualification. He can be reached at dcrothers@ndcourts.gov

Justice Crothers regularly conducts training for judges and lawyers on ethics and technology, and on judicial disqualification. He can be reached at dcrothers@ndcourts.gov