by Emily Krueger, MA (NCJFCJ) and Stephanie Macgill, MPA (NCJFCJ)

The Courts Catalyzing Change: Achieving Equity and Fairness in Foster Care Initiative (CCC), led by the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) in partnership with Casey Family Programs and supported by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, is a multidisciplinary collaborative effort. The CCC Initiative brings together judicial officers and juvenile dependency stakeholders to advance a National Agenda of reducing the disproportionate representation and disparate treatment of children of color in the child welfare system.

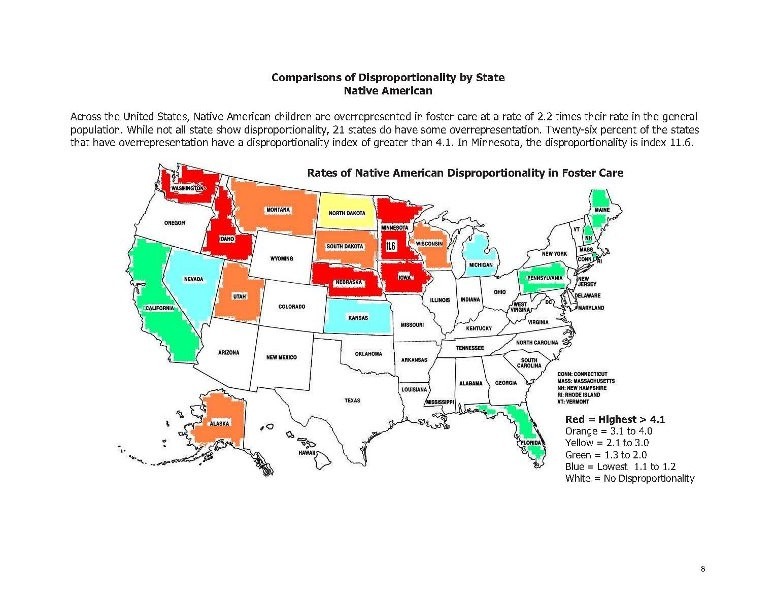

Disproportionality and disparity are distinct, complex, and related concepts. Disproportionality is created and perpetuated by disparities (SEE NOTE 1). Thus, “[p]olicies and practices to reduce disproportionality must target the underlying disparities that lead to it (SEE NOTE 2).” The National Incidence Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect-4 (NIS-4), reporting on data from FY2006, found that African American children experienced higher rates of maltreatment than white children in several categories; however, this is due in part to the “growing gap between white and black children’s economic well-being, (SEE NOTE 3)” which has led to research that children and families of color are disproportionately represented in the child welfare system (SEE NOTE 4). “In states where there is a large population of Native Americans, this group can constitute between 15% and 65% of the children in foster care. (SEE NOTE 5)” Hispanic or Latino children may be significantly over-represented based on the locality (e.g., in Santa Clara County, California, Latino children represent 30% of the child population, but 52% of all child welfare cases) (SEE NOTE 6). Also, African American children experience disparate decision-making in investigation, substantiation, removal, placement in foster care and final permanency determinations. “African Americans are investigated for child abuse and neglect twice as often as Caucasians, (SEE NOTE 7)” and African American children, who are determined to be victims of child abuse, are 36% more likely than Caucasian children to be removed from their parent(s) and placed in foster care (SEE NOTE 8). Federal Child and Family Services Review (SEE NOTE 9) data also show that Caucasian children achieve permanency outcomes at a higher rate than children of color (SEE NOTE 10). In addition to being more likely to be placed in foster care, African American children are less likely to be reunified with their parents (SEE NOTE 11) and receive fewer services than Caucasian children (SEE NOTE 12).

This data can feel overwhelming to those interested in addressing this problem. One must remember there are a number of factors that contribute to disparities. Agency practices, court culture, access to and effectiveness of services, child and family resources, risk factors associated with poverty, community resources, law and public policy, social problems, institutional/structural racism and individual bias may all be contributing factors. A “one size fits all” service array, found in far too many communities, belies the fact that the same services do not work for every family. Services that are targeted, culturally appropriate, and specific must be developed in communities across the country. Every person and part of the child welfare system must engage in targeted strategic action to reduce these inequities in order to improve outcomes for all children and families.

In an effort to work toward the goal of reducing disproportionality and disparate treatment in child welfare, judicial officers on NCJFCJ’s CCC Steering Committee, the Permanency Planning for Children Advisory Committee, and Victims Act Model Court Lead Judges workgroup developed a judicial decision making tool for use during the first hearing in a dependency case—the preliminary protective hearing (SEE NOTE 13). The Courts Catalyzing Change Preliminary Protective Hearing Benchcard (Benchcard) asks judges to reflect on their decision-making processes in order to mitigate the effects of institutional bias and to make key inquiries, analyses, and decisions relating to child removal, placement, and services for children and families.

After developing the Benchcard, the Permanency Planning for Children Department (PPCD) tested Benchcard effects. Through experimental and quasi-experimental research, PPCD researchers found that Benchcard use reduces the number of children placed in foster care at the first hearing. The researchers tracked more than 500 children through the court system in three cities and found that 45% more children were able to return home to their parents or live with extended family members when judges used the Benchcard during their hearings. The NCJFCJ is awaiting peer-reviewed publication of its results document, titled Right From the Start: The CCC Preliminary Protective Hearing Benchcard Study Report, as the final step to identifying Benchcard implementation as an evidence-based practice.

PPCD researchers tested the effects of Benchcard use in LA, Portland and Omaha and found that Benchcard use is associated with (a) increased quality and quantity of discussion of important dependency-related topics during preliminary protective hearings; (b) reductions in foster care placement rates; and (c) an increase in family placement rates (SEE NOTE 14). The Benchcard has also been implemented in other test sites and PPCD expects to publish more findings on the effects of Benchcard use in late 2012. The Model Courts are also using the Benchcard and PPCD will be assessing implementation progress in all dependency Model Courts in 2012.

Ongoing implementation of the CCC National Agenda includes convening a national Tribal Judicial Leadership Group with the goals of meaningful engagement with tribes and tribal courts by state courts, and improving state court compliance with the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). Also, in December 2011, NCJFCJ Model Court Lead Judges (and their designees) and key tribal partners will meet in Reno, Nevada, to discuss how NCJFCJ and its partners can assist state courts in achieving ICWA compliance. Another component of the CCC initiative is the updating and enhancing of the groundbreaking RESOURCE GUIDELINES publications. The updates and revisions are being developed through a race-equity lens, incorporating lessons learned from the CCC Benchcard implementation research, and incorporating legislation enacted since the original publication in 1995 of the RESOURCE GUIDELINES. Finally, at their March 2011 meeting, the CCC Steering Committee decided to expand their focus in this area by examining foster care licensing standards. The CCC Steering Committee chose this as an area to examine because licensing standards vary by state as some states choose to waive non-safety-related foster care licensing standards on a case-by-case basis for kin seeking to become foster parents. Furthermore, licensing standards can be cumbersome and may prevent the licensing of qualified foster parents and there is a common belief that some non-safety related standards unnecessarily hinder the ability of families of color to become foster parents. The Annie E. Casey Foundation has partnered with NCJFCJ on its efforts in this area.

The CCC initiative has come a long way since its initial discussion among judges and interested stakeholders. The PPCD will continue to offer its CCC Benchcard training as well as develop new curricula that will include the ongoing work of the CCC National Agenda. The Benchcard Study Report is the first report to be released, and as with all field research, the Benchcard Study Report notes limitations, but is one of several steps necessary for establishing the Benchcard as an evidence-based practice. The Benchcard study has not yet examined the impact of the hearing guidelines on different racial and ethnic groups. NCJFCJ sought first to measure the effectiveness of the Benchcard for all children before further analysis is conducted. The NCJFCJ will continue to track the results of the Benchcard implementation and is currently expanding its research as the guidelines are used in additional jurisdictions.

Emily Krueger, MA, is an Information Specialist at the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. She received a B.A. in Philosophy from Indiana University–Indianapolis, and a Master of Arts in Biomedical Ethics, also from Indiana University–Indianapolis. As an Information Specialist at the NCJFCJ, Ms. Krueger provides editorial, proofreading, and writing support for the department as well as maintains the PPCD section of the NCJFCJ website and researches technical assistance requests. Before she joined the NCJFCJ, Ms. Krueger worked for a large health and hospital corporation, located in Indianapolis, Indiana, where she was employed as a senior grant writer to assisted staff with the development of grant-related research methodologies and activities that included high-risk populations. Ms. Krueger also worked for the Indiana State Department of Health where she developed a social immersive media program that offers an innovative social marketing approach to increase public awareness of the importance of integrating the life-course perspective into preconception planning and care.

Emily Krueger, MA, is an Information Specialist at the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. She received a B.A. in Philosophy from Indiana University–Indianapolis, and a Master of Arts in Biomedical Ethics, also from Indiana University–Indianapolis. As an Information Specialist at the NCJFCJ, Ms. Krueger provides editorial, proofreading, and writing support for the department as well as maintains the PPCD section of the NCJFCJ website and researches technical assistance requests. Before she joined the NCJFCJ, Ms. Krueger worked for a large health and hospital corporation, located in Indianapolis, Indiana, where she was employed as a senior grant writer to assisted staff with the development of grant-related research methodologies and activities that included high-risk populations. Ms. Krueger also worked for the Indiana State Department of Health where she developed a social immersive media program that offers an innovative social marketing approach to increase public awareness of the importance of integrating the life-course perspective into preconception planning and care.

Stephanie Macgill, MPA, is a Research Associate with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. She holds a B.A. from Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts and a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Nevada, Reno. Prior to joining the NCJFCJ, Stephanie worked as an advocate for individuals experiencing homelessness in Boston and Reno, and studied federal and local homelessness policies. In her capacity as a Research Associate, Stephanie collaborates on research projects that seek to inform systems change and improve outcomes within the juvenile dependency court system.

Stephanie Macgill, MPA, is a Research Associate with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. She holds a B.A. from Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts and a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Nevada, Reno. Prior to joining the NCJFCJ, Stephanie worked as an advocate for individuals experiencing homelessness in Boston and Reno, and studied federal and local homelessness policies. In her capacity as a Research Associate, Stephanie collaborates on research projects that seek to inform systems change and improve outcomes within the juvenile dependency court system.

NOTES

1 Gatowski, S., Maze, C., & Miller, N. (Summer 2008). Courts Catalyzing Change: Achieving Equity and Fairness in Foster Care — Transforming Examination into Action. Juvenile and Family Justice TODAY, 16-20

2 Ibid.

3 Sedlak, A. J., McPherson, K., & Das, B. (2010). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4): Supplementary analyses of race differences in child maltreatment rates in the NIS-4. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

4 Anderson, G. R. (1997). Introduction: Achieving permanency for all children in the child welfare system. In G. R. Anderson, A. Ryan, & B. Leashore (Eds.), The challenge of permanency planning in a multicultural society (pp. 1-8). New York: Haworth Press, Inc. See also U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2005). Data Report.

5 Miller, O. (2009). Breakthrough Series Collaborative on Reducing Disproportionality and Disparate Outcomes for Children and Families of Color in the Child Welfare System. Casey Family Programs. Seattle: WA. Retrieved at http://www.casey.org/Resources/Publications/pdf/BreakthroughSeries_ReducingDisproportionality_ process.pdf on June 10, 2010.

6 Congressional Research Service. Race, Ethnicity and Child Welfare (August, 2005).

7 Yaun, J., Hedderson, J., and Curtis, P. (2003). Disproportionate representation of race and ethnicity in child maltreatment investigation and victimization. Children and Youth Services Review, 25, 359-373.

8 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2005). Data Report.

9 The Child & Family Service Review (CFSR) are a statewide assessment and on-site review by the Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children & Families Children’s Bureau. The state must address a large array of systemic factors that are reviewed by the federal team of reviewers. The process includes case file reviews, consumer interviews, stakeholder interviews and state data analysis and review. The states are measured in the area of safety, permanency and child and family well-being. For more information on the CFSR process, visit www.acf.dhhs.gov\programs\cb.

10 National Child Welfare Resource Center (2006). Data Report.

11 Lu, Y. E., Landsverk, J., Ellis-MacLeod, E., Newton, R., Ganger, W., & Johnson, I. (2004). Race, ethnicity and case outcomes in child protective services. Children and Youth Services Review, 26, 447-461. 12 Courtney, M., Barth, R., Berrick, J., Brooks, D., Needell, B., & Park, L. (1996). Race and child welfare services: Past research and future directions. Child

13 The preliminary protective hearing may be called a shelter hearing, the initial hearing, or the detention hearing, depending on the jurisdiction.

14 National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. (2011). Right from the start: the CCC Preliminary Protective Hearing Benchcard study report. Reno, NV.

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) Juvenile Justice Model Courts Project, managed by the Juvenile and Family Law Department, has expanded the number of courts participating in the project to 12. Four of the recently added sites in the project (Pittsburgh, Pa., State of Minnesota; New Orleans, La.; and Memphis, Tenn.) are developing goals and addressing challenges to achieve the recommendations from the

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) Juvenile Justice Model Courts Project, managed by the Juvenile and Family Law Department, has expanded the number of courts participating in the project to 12. Four of the recently added sites in the project (Pittsburgh, Pa., State of Minnesota; New Orleans, La.; and Memphis, Tenn.) are developing goals and addressing challenges to achieve the recommendations from the

Gina Jackson, MSW, is a Model Court Liaison for the Victims Act Model Court Project with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges working with several jurisdictions across the country. Ms. Jackson belongs to the Temoke Western Shoshone Tribe. She holds a Masters and Baccalaureate degree in Social Work from the University of Nevada, Reno, with a minor in Early Childhood.

Gina Jackson, MSW, is a Model Court Liaison for the Victims Act Model Court Project with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges working with several jurisdictions across the country. Ms. Jackson belongs to the Temoke Western Shoshone Tribe. She holds a Masters and Baccalaureate degree in Social Work from the University of Nevada, Reno, with a minor in Early Childhood. Emily Krueger, MA, is an Information Specialist at the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. She received a B.A. in Philosophy from Indiana University–Indianapolis, and a Master of Arts in Biomedical Ethics, also from Indiana University–Indianapolis. As an Information Specialist at the NCJFCJ, Ms. Krueger provides editorial, proofreading, and writing support for the department as well as maintains the PPCD section of the NCJFCJ website and researches technical assistance requests. Before she joined the NCJFCJ, Ms. Krueger worked for a large health and hospital corporation, located in Indianapolis, Indiana, where she was employed as a senior grant writer to assisted staff with the development of grant-related research methodologies and activities that included high-risk populations. Ms. Krueger also worked for the Indiana State Department of Health where she developed a social immersive media program that offers an innovative social marketing approach to increase public awareness of the importance of integrating the life-course perspective into preconception planning and care.

Emily Krueger, MA, is an Information Specialist at the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. She received a B.A. in Philosophy from Indiana University–Indianapolis, and a Master of Arts in Biomedical Ethics, also from Indiana University–Indianapolis. As an Information Specialist at the NCJFCJ, Ms. Krueger provides editorial, proofreading, and writing support for the department as well as maintains the PPCD section of the NCJFCJ website and researches technical assistance requests. Before she joined the NCJFCJ, Ms. Krueger worked for a large health and hospital corporation, located in Indianapolis, Indiana, where she was employed as a senior grant writer to assisted staff with the development of grant-related research methodologies and activities that included high-risk populations. Ms. Krueger also worked for the Indiana State Department of Health where she developed a social immersive media program that offers an innovative social marketing approach to increase public awareness of the importance of integrating the life-course perspective into preconception planning and care. Stephanie Macgill, MPA, is a Research Associate with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. She holds a B.A. from Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts and a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Nevada, Reno. Prior to joining the NCJFCJ, Stephanie worked as an advocate for individuals experiencing homelessness in Boston and Reno, and studied federal and local homelessness policies. In her capacity as a Research Associate, Stephanie collaborates on research projects that seek to inform systems change and improve outcomes within the juvenile dependency court system.

Stephanie Macgill, MPA, is a Research Associate with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. She holds a B.A. from Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts and a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Nevada, Reno. Prior to joining the NCJFCJ, Stephanie worked as an advocate for individuals experiencing homelessness in Boston and Reno, and studied federal and local homelessness policies. In her capacity as a Research Associate, Stephanie collaborates on research projects that seek to inform systems change and improve outcomes within the juvenile dependency court system.