NASJE members who want an easy way to get their questions out to the judicial education community should consider using NASJE’s List Serve, which can send a message to all NASJE members at once. Please see the “Other Resources” area of the Member Area for instructions.

Blog

-

Karen Thorson Award Nominations Due March 31

Karen Thorson Karen Thorson Award nominations are now being accepted by the NASJE Board.

If you know a career judicial educator who has made significant contributions to the profession and to NASJE, consider nominating him or her for this award. Nominations are due by Friday, March 31, 2017. You will find a link to the nomination form in the Forms section of the NASJE Member Area.

Last year’s winner was Jim Drennan of North Carolina, and you can see the article about his distinguished career here.

The award, established in 2012, strives to recognize members who have had an impact nationally on judicial branch education, on the profession, and in NASJE. Previous winners include Karen Thorson, Maureen Conner, and Larry Stone.

-

Longtime Educator Diane Cowdrey Retires

By Nancy Fahey Smith

After nearly 28 years in Judicial Education, Diane Cowdrey of California has retired.

Diane Cowdrey Diane began her career in adult education by preparing adults in a mental institution to pass their GED. Diane says, “This job was the first time I realized there was a career teaching adults.” She reflected, “At that time adult education was just beginning to be a field of endeavor.” In 1988, while working on the area of continuing professional education in graduate school, she launched herself into judicial education via a State Justice Institute grant that had as its goal to provide funding for states and universities to strengthen judicial education efforts. Diane worked on the Judicial Education/Adult Education Project (JEAEP) at the University of Georgia. Upon graduating with her Ed.D. in Adult Education, Diane became the director of the JEAEP project and worked with Richard Reeves and Dr. Ron Cervero. She also learned about NASJE and began learning what it meant to be a judicial educator.

At the behest of Justice Christine Durham of the Utah Supreme Court, Diane applied for the position of Director in the Utah AOC. She was hired and remained there for 15 years. Eight years ago, California’s Judicial Council hired her to be the Director of the California Center for Judicial Education and Research (CJER). She retired as of December 31, 2016.

Utah’s small size allowed Diane to get to know all the judges in the state, and she developed personal relationships with the people she served. The small size and centralized nature of the Utah judicial system allowed Diane and her team to try many innovative statewide projects. The state court administrator, Dan Becker (who will retire this spring) is a big supporter of judicial education. Dan and Justice Durham played key roles in Diane’s success with their strong support. Utah also encouraged involvement in national organizations, allowing Diane to serve on projects with the Judicial College, the American Judicature Society, and NASJE, as well as serving on the Advisory Board of ICM. The National Center honored her with its Distinguished Service Award in 2006. Diane also had the opportunity to teach judges and court staff in Macedonia through a US-AID funded project.

At CJER, Diane worked with an incredible team, as well as with over 700 members of the judicial branch who serve as faculty. She could not say enough about her staff and their professionalism and commitment to their work. Her time at CJER was both exciting and demanding, with budget reductions, layoffs and structural changes in the AOC occurring during her tenure. Diane became a master of change! She also built upon the solid base Karen Thorson left behind when she retired from CJER. From that base, Diane developed a two-year planning cycle for education, and conducted resource analysis to quantify the financial and staffing resources necessary to complete the plan, forcing committee chairs to prioritize projects that became judicial education. Judge Theodore M. Weathers, current Chair of the Governing Committee for CJER and member of the San Diego Superior Court, expressed his pleasure at working with Diane, calling her, “A true champion of education for the judicial branch in California.” Judge Weathers noted that during the last Education Plan, Diane and her staff produced over 200 separate statewide and regional in-person courses and programs, as well as nearly 200 distance mediated education products, including videos, broadcasts, webinars, and online courses. He praised her leadership in innovative education delivery methods, calling it, “An honor and a pleasure to work with my friend, Dr. Diane Cowdrey.” Judge Ron Robie, former Chair of the Governing Committee and Associate Justice in the California Courts of Appeal echoed Judge Weathers’ comments, saying “She was an excellent manager even though the branch was decimated by budget cuts and uncertainty. She kept CJER the premier state [judicial] education program.” Both Chairs encouraged CJER to use technology to increase the options for delivering judicial education and to appeal to judges who like receiving education in that way. Diane and her staff immediately saw the value in using technology and as a result, CJER just launched a series of podcasts for California judges and will shortly allow judges to subscribe to automatic updates in their website, CJER Online.

Diane has seen many changes in Judicial Education since she came on board. In her opinion, technology offers both challenges and opportunities for educators. The drive for data and the bureaucratization of education will transform the way educators do business. She also sees the current nationwide movement in Criminal Justice reform as a pivotal moment both for the courts and for judicial branch educators.

Diane credits NASJE with the professionalization of judicial branch education, and is thankful for the network of colleagues NASJE provided for her during her career. “That network of support,” she says, “hasn’t changed over the years.” She sees that judicial education has evolved into a real profession, and continues to move in the direction of more grounding in educational principles and theory. This move can only increase the effectiveness of judicial branch education. With so many states in constant need of resources, it can be all too easy to forget that the focus of judicial education must be on effectiveness and not simply on efficiency. Diane believes our profession is critical to helping ensure the fair administration of justice in our country, and has been grateful for the opportunity to serve in such a profession, and with incredible judges, court staff and members of her team.

She can be reached at coyotehealth@comcast.net.

-

Judging Science in the Courthouse

By Judge Brian MacKenzie

“Scientific evidence permeates the law” according to Justice Stephen Breyer (see note 1). His statement was specifically about scientific evidence in a trial. However, trials are not the only place where judges are being pressed to understand and then use the ever-expanding universe of research based knowledge that is available. While present in hearings and trials, there has been a particularly strong move to have judges apply such information in sentencing and probation supervision. The development of evidence-based sentencing, a concept based on a medical model, is merely one example (see note 2).

This expanding universe of scientific knowledge has engendered many discussions about the perceived need to increase the amount of science based education judges receive. Some argue that judges should be educated like scientists. The problem intrinsic this idea is that judges are specialists in the law, and generalists in everything else. Moreover, the vast majority of judges turned away from a scientific education, at least by the time they were in college and certainly by the time they were in law school. Law school teaches a different manner of seeking the truth than the scientific method.

After all, what scientist would accept a scientific proposition that while approximately 90% of people arrested will be convicted of a crime, each of these

people starts with the presumption that they are innocence of the charges? Beyond inclination and education, there is the question of time. Most judges are lucky if they receive two or three days of judicial educational during the course of the year. Much of that educational time is spent on updates on the current state of the law. Nonetheless, it is true that judges need to be given the tools to help them process scientific information in their different

roles as what Justice Breyer calls “evidentiary gatekeepers” and as “finders of reality based facts (see note 3).”These different roles suggest there should be different educational approaches. When the judge is acting as an evidentiary gatekeeper, (for example, deciding whether the results of a drug test should be admitted in a trial) a thorough understanding of the rules on the admissibility of scientific evidence would be helpful. A judge who is sentencing a defendant and is trying to assess that person’s future behavior needs yet a different understanding — one based more on psychology and social science.

How does the judicial education community meet the varied educational needs of the judiciary? It starts with the recognition that judges are specialists in the law and generalists in everything else. As part of that legal specialization judges are the evidentiary gatekeepers for any scientific or technical evidence that is admitted in a trial. As the Supreme Court stated: “Daubert‘s gatekeeping requirement is to make certain that an expert, whether basing testimony upon professional studies or personal experience, employs in the courtroom the same level of intellectual rigor that characterizes the practice of an expert in the relevant field” (see note 4).

Providing judges with the tools to make better evidentiary decisions about the admissibiity of scientific evidence will also ensure that the trier of fact is not confused by poor or junk science. Gatekeeping will not help a judge better understand the emerging science about addiction when it comes to sentencing. Neither will it help with a risk assessment about a defendant’s future conduct. But, as sentencing is a part of the specialized training judges already receive, there is a wealth of training and conferences on this topic. For example, one need only look at the National Association of Drug Court Professionals annual conference for trainers who teach about every aspect of addiction and sentencing.

Still, not every judge has either the time or the interest to attend a national training. How can we better assist the judiciary in dealing with this flood of scientific evidence? One answer was developed by our colleagues in Canada created a bench book entitled the “Science Manual for Canadian Judges” (see note 5). Bench books and the trainings connected to them are an excellent means for helping judges keep current with the needs of their job. NAJSE should take a leadership role in creating such a manual.

NOTES

- Justice Stephen Breyer,“Science in The Courtroom” Issues In Science And Technology, 2000

- Sonja B. Starr, “Evidence-Based Sentencing And The Scientific Rationalization Of Discrimination” Stanford Law Review, Vol. 66:803, 2014

- Breyer, note 1

- Ibid

- “Science Manual for Canadian Judges” NATIONAL JUDICIAL INSTITUTE, INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA MAGISTRATURE, 2013

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Judge Brian MacKenzie is an award winning judicial educator who retired from the bench after almost twenty-seven years of service. After leaving the bench he helped to create the Justice Speakers Institute where he is now a partner and chief finical officer. He has been honored by the Foundation for the Improvement of Justice with the Paul H. Chapman medal, for significant contributions to the American Criminal Justice System and by the American Judges Association for significant contributions to judicial education. Judge MacKenzie served as the President of the American Judges Association from 2014 to 2015. From 2008 to 2010 Judge MacKenzie was the American Bar Association/National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Judicial Fellow. He received his Juris Doctorate from Wayne State University Law School in 1974. Judge MacKenzie has written and lectured throughout the world on issues including procedural fairness, veterans treatment courts, domestic violence, drug treatment courts, alcohol/drug testing, and high visibility cases. Among other entities he has presented for American University, the National Judicial College, the National Association of Drug Court Professionals, the American Judges Association, the American Bar Association, the National Traffic Safety Administration, and the National Association of Court Managers. He is the co-editor of the book, “Michigan Criminal Procedure”. He is also the author of the American Judges Association’s position paper entitled “Procedural Fairness: The Key to Drug Treatment Courts”. His blog and podcast can be found at http://justicespeakersinstitute.com/. Judge MacKenzie is married to Karen MacKenzie. He has three children; Kate, David and Breanna and five grandsons, Daniel, Raymond, Henry, Zachary and Lucas.

Judge Brian MacKenzie is an award winning judicial educator who retired from the bench after almost twenty-seven years of service. After leaving the bench he helped to create the Justice Speakers Institute where he is now a partner and chief finical officer. He has been honored by the Foundation for the Improvement of Justice with the Paul H. Chapman medal, for significant contributions to the American Criminal Justice System and by the American Judges Association for significant contributions to judicial education. Judge MacKenzie served as the President of the American Judges Association from 2014 to 2015. From 2008 to 2010 Judge MacKenzie was the American Bar Association/National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Judicial Fellow. He received his Juris Doctorate from Wayne State University Law School in 1974. Judge MacKenzie has written and lectured throughout the world on issues including procedural fairness, veterans treatment courts, domestic violence, drug treatment courts, alcohol/drug testing, and high visibility cases. Among other entities he has presented for American University, the National Judicial College, the National Association of Drug Court Professionals, the American Judges Association, the American Bar Association, the National Traffic Safety Administration, and the National Association of Court Managers. He is the co-editor of the book, “Michigan Criminal Procedure”. He is also the author of the American Judges Association’s position paper entitled “Procedural Fairness: The Key to Drug Treatment Courts”. His blog and podcast can be found at http://justicespeakersinstitute.com/. Judge MacKenzie is married to Karen MacKenzie. He has three children; Kate, David and Breanna and five grandsons, Daniel, Raymond, Henry, Zachary and Lucas. -

Report of the Education and Curriculum Committee

Judith Anderson The Education and Curriculum Committee is hard at work on a number of initiatives designed to enhance the professional lives of judicial educators. The fifteen-member committee, co-chaired by Judith Anderson of Washington and Anthony Simones of Missouri, made the decision to split into three subcommittees in order to effectively achieve the goals of the group.

The first goal is to propose curriculum-based sessions for the 2017 NASJE Conference. The subcommittee that took on this task included Kelly Tait, Janice Calvi-Ruimerman, Marie Anders, Stephanie Hemmert, Dana Bartocci, Judith Anderson and Anthony Simones. After reviewing the sessions offered at recent conferences, a number of needs were identified. One session will examine why the curriculum designs were created and how they can be used by judicial educators to enhance the quality of their work. A second session will address the always-relevant topic of diversity issues. A third session will explore success in writing grant applications. Finally, a much-needed session will deal with the Human Resources Curriculum Design. Workgroups are currently creating proposals for these sessions to be submitted to the Conference Committee.

Anthony Simones A second goal is to continue what has come to be known as the “Article Club.” Created last year, it was inspired by the success of book clubs throughout the nation. However, the idea of asking busy judicial educators to find the extra time to read a book to prepare for a single meeting struck the committee as unrealistic. On the other hand, simply asking them to read an article in preparation for a session was much more realistic. Thus, the initial idea of a “book club” became a much more practical “article club.” Another modification of the status quo involved the “webinar” format. The visual-heavy focus of webinars seemed ill-suited to what the committee sought to accomplish with these sessions: the simple sharing of ideas. It was decided that a conference-call format would be much more conducive to achieving this objective. Thus, the “callinar” was born. The two sessions were well-received last year and two more callinars will be offered in 2017. The subcommittee charged with offering the article club callinars includes Julie McDonald, Thea Whalen, Linda Dunbar, Judith Anderson and Anthony Simones.

A final goal is to identify and to lay the foundation for the creation of the next curriculum design: ethics. The subject of ethics is one that has permeated all of the existing curriculum designs. The committee concluded that rather than just occupy a small section of the various curriculum designs, this issue is one that justifies its own curriculum design. Jeff Schrade, Jesse Walker, Janice Calvi-Ruimerman, Ileen Gerstenberger, Stephen Feiler, Christine Christopherson, Judith Anderson and Anthony Simones comprise the subcommittee that will address this issue. The first step will be to develop a core curriculum on ethics. After this, the group will wrestle with a number of issues involved in the creation of the Ethics Curriculum Design, including the designation of an author, as well as the question of whether to continue the structural approach used in the past curriculum designs.

The agenda of the Education and Curriculum Committee has been characterized as ambitious. Given the importance of the issues this committee addresses, and the quality of the individuals who compose this group, it is difficult to imagine anything less than an ambitious agenda for this committee.

If you are interested in getting involved with the Education and Curriculum Committee, please feel free to contact co-chairs Judith Anderson at judith.anderson@courts.wa.gov or Tony Simones at anthony.simones@courts.mo.gov.

-

From the President (Winter 2017)

To my NASJE colleagues:

NASJE President

Caroline KirkpatrickAs if you need any more reminders that the new year is upon us…I’m going to add my well wishes for a happy, healthy, educational 2017! So often, we think about January as a time for looking forward, planning the year, determining what we will do better or what we will do more of. While engaged in some of this self-reflection, I was reminded of a conversation with a colleague that took place a few months ago, and began with a simple question – “How is your NASJE presidency going?” My colleague then added, “I’ve heard that there are two types of leaders – ones who attempt to steer the ship in a new direction, forging new paths, and ones who simply attempt to keep the ship off of the rocks.” While my ambition certainly does not completely align with “simply keeping the ship off of the rocks,” I hardly see the need for a new direction or a new path. NASJE has continued to grow and evolve since its inception in 1973, into an organization that is recognized nationally and internationally for its commitment to advancing the administration of justice through excellence in judicial branch education.

Looking back on 2016, I was reminded of “Sleepless in Seattle,” but not because of the movie, but rather because of the formatting of the title. I think it’s mostly because a similarly formatted phrase…“Pining for Burlington”…seems to characterize my feelings to a tee! The weather was beautiful, the connections and friendships even more solidified and the professional renewal was at work once again. I don’t know about other members who took part in NASJE’s annual conference in beautiful Burlington, but I for one have already used some good tips here in Virginia. Please take this opportunity, if you have not already, to look over your conference information, including all of the resources available in the cloud, and take some action. Do one thing to pay forward all of the good education and work that occurred in Vermont. For those of you who couldn’t attend, you are also being called to action. The conference materials are available in the “Members Only” section of nasje.org, so please take a look when you have a minute. NASJE’s utility reaches far beyond conference attendance – we can continue to grow, learn and network throughout the year in a variety of ways.

Let’s recollect some of these ways, so that we can begin to plan on attending and participating in as many of them as possible:

- Familiarize yourself with the committee list and contact a chair to see how you can get involved; the monthly schedule of committee calls can be found on the NASJE calendar.

- Continue to visit nasje.org regularly as articles, book reviews, videos and other educational resources and announcements are posted.

- Use the listserv to ask questions about what other states are doing and share if something has worked particularly well for you and your judicial branch “consumers.”

- Consider submitting a proposal for a conference workshop or session at “other” education or court related conferences. Let related communities benefit from NASJE members’ expertise and collective knowledge.

- Help increase our social media presence and value by “sharing” and “liking” articles, court community events, colleagues’ accolades, and studies that promote healthy discussion and reflection.

One last idea, if I may…begin thinking now about ways to increase the likelihood of your attendance at the 2017 annual conference in Charleston. As indicated above, it is but one way to stay connected and involved in NASJE, but I suspect there are few educational experts who would deny the awesome power of face to face interaction and connections. Are there topics you could present during a breakout session? Are there topics or areas of concern that could be suggested for the 2017 program that might help persuade “the powers that be” to support your attendance? Can the NASJE conference registration fee be earmarked now for any funds that are saved during the year or that remain at the end of the fiscal year? Would you be willing to fund some portion of attendance, demonstrating your commitment to the profession AND your agency or organization? Unfortunately, many of us have little control over budgets or out of state travel policies, but we all benefit when conference attendance is high and diverse. More ideas, more examples, more tips and best practices…it’s a win win, so start thinking now of ways to increase your likelihood of being South Carolina bound next September.

I appreciate so much the opportunity to serve as NASJE’s President and feel confident that with your support and the guidance of the Board and other past and present NASJE leaders, our ship will stay the course. Let’s make 2017 another unforgettable year for ourselves and our organization!

-

Phil Schopick Retires at Year End

Phil Schopick After more than 25 years in Judicial Branch education, Phil Schopick of the Supreme Court of Ohio Judicial College is retiring.

Phil was editor of NASJE News (the predecessor of our news and information website) for about 10 years and was active in NASJE on the international committee and communications committee.

In Ohio Phil is the education program manager for magistrate education (Ohio elects judges; magistrates are appointed by individual judges), acting judge education, and capital case education. Phil’s career included a large distance learning component: he planned and produced audio and video teleconferences as well as satellite and web-based programs.

Phil says he is retiring, but is not tired. At a minimum, he will focus on his ACT and SAT teaching and tutoring business for high school juniors and seniors, which he has done in person and over the phone for almost 30 years. Everyone is welcome to keep in touch with him at Phil@SchopickTestPrep.com. NASJE members can find more contact information for Phil in the member area.

Editor’s Note: if you have news about changes in status, either promotions or retirements, please share them with your NASJE colleagues. Please send your updates to lynne.alexander@courts.mo.gov.

-

Tax-deductible contributions to NASJE

NASJE President Caroline Kirkpatrick Dear NASJE Colleagues,

As I receive solicitations from other associations and organizations, I am reminded of my duties as NASJE’s President to … promote the growth of NASJE and the strengthening of its position within the court community and ensure NASJE’s fiscal viability.

I am also reminded of NASJE’s mission: [to advance] the administration of justice by providing support, education, and resources to educators who develop quality continuing education for judicial officers and judicial branch personnel.

Funding, of course, helps NASJE achieve its mission.

If you find yourself looking for a tax deduction during the remaining days of 2016, NASJE’s website has information on how to donate to the association. Please check the right column of almost any page on the website for the DONATE button.

On behalf of the Board – thank you for all of your contributions to NASJE, whether they are monetary ones or ones related to committee membership, conference attendance, webinar attendance, providing mentorship to newer judicial educators, or sharing your knowledge as a presenter at a NASJE event. As they say, it takes a village.

Happy Holidays!

Caroline E. Kirkpatrick, Ph.D, NASJE President

-

Rethinking Learning Styles: Judicial Educators as Restless Learners

By Nancy Fahey Smith, Pima County Field Trainer (Tucson, AZ) and Director, NASJE Western Region

The restless learner—a person who can never be comfortable with her/his own expertise in the face of rapid knowledge advancements, research revisions, and obsolescence of facts.

—from Warren Berger, The More Beautiful Question (2014)Judicial Branch Educators are restless learners. As such, they continually investigate new research on teaching and learning and on topics of interest to courts. They also need to be critical thinkers, constantly evaluating what they know and what they need to learn. Rethinking learning styles is just such a topic. There is much to know about learning styles, but well-tested and documented research goes against the widely accepted view that teachers should alter their teaching styles according to their learners’ learning styles in order to maximize learning. In addition, research casts doubt on the reliability of assessments designed to determine individual learning styles. In this article, the video that was the impetus for the session on this topic at NASJE’s 2016 conference will be summarized, a review of research on these topics will be discussed, and possible implications for NASJE members will be put forth.

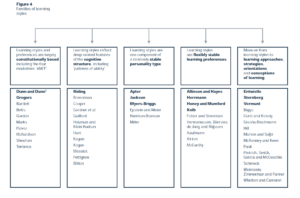

First of all, how are learning styles defined? Essentially, this is part of the problem. The definition varies widely depending on which of many models one consults. Coffield et al., in the comprehensive “Learning Styles and Pedagogy in Post-16 Learning: A Systematic and Critical Review,” grapple with this issue and end up categorizing the many models into five different families (Coffield, 10).

(click for larger image) Regardless of the definition of learning styles, the most popular recommendation in the models is that teachers should match their teaching style to the learning styles of their learners. How does a teacher know the learning style of a learner? By using a learning style assessment (LSA) or learning style inventory (LSI), or similar measuring tool.

With the complexity of these models in mind, a good way to begin an open discussion about the limited usefulness of learning styles theory in the development of classes, courses, or programs, is to view the 2015 TEdx Talk by Dr. Tesia Marshik called “Learning Styles and the Importance of Self-Reflection.” In it, Professor Marshik of the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse explains that we believe learning styles theory because the idea is so widespread that one might think, “How can so many people be wrong?” The idea seems so logical, it must be true! Many teacher training and faculty development programs include a discussion of learning styles theory and what teachers should do with respect to them. Because we are so convinced, we have something called confirmation bias. This means that since we want to believe a theory is true, we look for information that confirms our belief. But research into how people learn, Dr. Marshik points out, shows that people store information as meaning, and thus, they learn better not because a given teaching method matches their learning style, but because the teaching method helps learners create meaning.

In the video, Dr. Marshik demonstrates with several examples that it is not a person’s learning style or the way a teacher changes styles to match those of learners that increases learning. Instead, it is the context a learner brings to the table, and teaching methods that help learners achieve desired learning outcomes that makes a difference. For example, does it make sense to teach birdsongs by showing pictures of birds, because the learners have identified as visual learners? Of course not.

Better, says Dr. Marshik, to teach in ways that enhance the intended outcome of the teaching. Clearly, learners would need to hear birdsongs if they are to identify the songs. Similarly, they would need to see birds, or pictures of them, to help match the song to the kind of bird. In fact, Dr. Marshik points out that seeing pictures of birds, listening to their songs, and observing live birds (perhaps on a field trip?) or videos of birds singing would enhance the chances of learners actually identifying the birds and their songs because involving more senses has been proven to enhance learning, possibly because it helps create meaning. This phenomenon is not, however, due to different learning styles, rather it is true that all people, regardless of learning style, learn better if more senses are involved. In a similar way, if the outcome is for learners to be able to change a flat tire, actually having the experience of changing the tire, coupled with instruction, will give the exercise meaning. But this method doesn’t work just for or particularly for kinesthetic learners, rather having the experience enhances the ability to change a tire for all learners.

Dr. Marshik does not mean to say that people aren’t different or that they don’t learn differently, only that teaching to someone’s learning style does not enhance their learning. Learning styles are usually self-assessed, and teaching someone only to their chosen style is limiting. It inhibits the ways learners can learn rather than enhancing learning by a variety of means. And, it is impractical for teachers to do.

Finally, Dr. Marshik points out the importance of context to learning. In an experiment using chess boards and experienced chess players, researchers demonstrated that the chess players remembered the position of chess pieces on a board very well if the board represented a realistic game. By contrast, if the pieces were placed randomly on the board they lost their contextual meaning, and the players were unable to recreate with much accuracy where the pieces were placed. The random nature of their position on the boards negated the meaning (context) for players. As educators, it is essential to remember the importance of the context learners bring to the classroom. If context is lacking, it must be established before learners will be able to make meaning during the learning process.

In “Learning Styles and Pedagogy in Post-16 Learning: A Systematic and Critical Review,” authors Coffield et al., set out to evaluate a large number of models that claim to prove learning styles theory and offer models that classify the learning styles of students. Coffield and company studied 13 out of 71 such models in five different groups. (NOTE 1: A total of 3800 references were identified; 838 were reviewed and logged in the database; 631 texts selected in the references, and 351 texts referring directly to the 13 major theorists. See Coffield et al., Figure 1.) Their research states that there is a dearth of well-conducted experimental studies of the models. The learning styles assessments themselves have proven to be unreliable and often invalid. Their conclusion? There is no evidence that ‘matching’ teaching styles to learning styles improves academic performance. In fact, in the explanations of the learning theories, the implications for teaching are drawn from the theories themselves rather than from research findings. In other words, pedagogical advice in various learning style theories may be logical, but is unproven. The wide variety of models, the vested interests in purveyors of learning styles assessments, and the entire theoretical framework has not made a proven difference in the efficacy of education for many learners.

Coffield and his co-authors did not throw out those 71 theories as total bunk. Each model is carefully explained in terms of strengths and weaknesses. They agree that teaching learners ways to talk about how they learn and what motivates them, as espoused by Kolb, can be beneficial to their learning. Their conclusion, however, is the same: adapting teaching styles to learning styles does not enhance learning and given the complexity of the task, is impractical to undertake.

What about Kolb’s learning circle? Is it a workable model if one takes away Kolb’s four learning styles named diverging, converging, accommodating and assimilating and just leaves the cycle of learning he espouses in this circle? Coffield et al. say the value of the learning circle is a big maybe. The flexible approach to learning styles Kolb puts forth is a plus, and experiential learning theory is seen as a strength of the model. But the Learning Styles Inventory has proven to be neither reliable nor valid, although it has improved in more recent iterations, and the learning circle itself may not be applicable to all learning as is proposed by the model. Since the implications for teaching in Kolb have not been conclusively proven in research findings, it is difficult to know how well it works (68, 70). The research is decidedly mixed. Like much in learning styles theory, the concept is logical and appealing while in reality, further well-designed studies are needed to prove that the model can be relied upon.

In “Do Learners Really Know Best? Urban Legends in Education,” (2013) Paul Kirschner and Jeroen van Merriënboer of the Open University of the Netherlands Department of Educational Development and Research call learning styles theory an “urban legend” based on belief rather than science, and used by instructional designers, curriculum reformers, politicians, school administrators and advisory groups all vying for position to show how innovative and up to date they can be. Kirschner and van Merriënboer examine three problems with learning style theory in their article. First, they explain that most learning styles are based on types, which means they classify people into distinct groups rather than assigning people scores on different dimensions. Objective studies, such as one by Druckman and Porter in 1991, do not support this way of labeling people. In reality, many people do not fit one particular style, the way they are classified relies on inadequate information, and there are so many different styles that it is difficult to link particular learners to particular styles.

A second problem with the “urban legend” are the low reliabilities of the measuring instruments. In other words, when individuals complete a particular measurement at two different points in time, the results are very often inconsistent (Stahl, 1999). Research also calls into doubt the validity of the learning styles measure—the relationship between what people say about how they learn and how they actually learn is weak.

A final point according to Kirschner and van Merriënboer is the proliferation of reported learning styles, as seen above in the Coffield study. How can teachers ever truly accommodate so many different styles as proposed in so many theoretical constructs? The research to prove which of the theoretical constructs is actually best has not been done.

In 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology (2010), Scott Lilienfeld and his co-authors make the same point, calling learning styles theory a myth, a scientific misconception. In the preface to the book, science educator David Hammer describes the four major properties of these kinds of misconceptions: 1. They are stable and often strongly held beliefs about the world; 2. They are contradicted by well-established evidence; 3. They influence how people understand the world; and 4. They must be corrected to achieve accurate knowledge. (Lilienfeld, et al. xiv). In their discussion, the authors arrive, after a review of the research, at the same conclusions as the Coffield group: The proliferation of learning styles models show no agreement about what learning styles are; learning styles inventories are not reliable, nor are they valid; there are not reliable studies showing that it helps students if teachers match their teaching styles to students’ learning styles. As the authors say, “models and measures of LS (learning styles) don’t come to grips with the possibility that the best approaches to teaching and learning may depend on what students are trying to learn.” (95). Clearly one would not choose to learn, nor to teach, ballroom dancing the same way as a foreign language or geometry theorems.

Popular education blogger Cathy Moore comes to the same conclusion about learning styles in her 2010 blog post “Learning Styles: Worth our Time?” and the Debunker Club is on a mission to convince teachers and others about the fallacy of their belief in learning styles in their “Learning Styles are NOT an Effective Guide for Learning Design.” They provide numerous references for further research supporting their view.

Essentially, while much good research exists that disproves learning styles theory, little good research proves that learning styles have value for teaching.

What does this mean for NASJE members, who learned about learning style theory in their new educators’ workshop and possibly in teacher education programs, and who hold to Kolb’s theories for support in their published instructional design and faculty development curricula? This is something each member will have to decide independently after doing their own research and examining what they teach, how they teach it, and why. In addition, NASJE as an organization should assess the value of teaching learning styles theory to new educators and new faculty, as well as decide how to approach faculty that have already been taught the theory and been asked to hold to it when designing their classes for judicial branch personnel.

What it does not mean, however, is that NASJE’s judicial branch educators have been teaching its members and its learners all wrong. To the contrary, many highly effective educators belong to this group. The NASJE curriculum design for instructional design, for example, teaches a logical progression for designing classes, considerations for developing learning objectives and outcomes, the importance of active learning and student involvement, a variety of teaching methodologies, evaluations, and much more valuable information at both a beginning and an advanced level. NASJE educators recognize the value of knowing their audience, and designing and teaching with their needs in mind. Rethinking learning styles is a way to advance the professionalism espoused by NASJE, and to embrace being “restless learners” who think critically and are not afraid rethink how they teach and learn.

NASJE members and judicial branch educators everywhere are encouraged to continue the discussion on the Judicial Educators Facebook page. In addition, posts about teaching methods that do work would be welcome. For those who do not yet belong to the group, search for “judicial educators” from your Facebook page and request to join the group. If you are not yet on Facebook, it is easy to join at facebook.com.

Resources/References

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E., & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post 16 learning: a systematic and critical review. The Learning and Skills Research Centre. See: http://sxills.nl/lerenlerennu/bronnen/Learning%20styles%20by%20Coffield%20e.a..pdf

Kirschner, P., van Merriënboer, J., (2013). Do Learners Really Know Best? Urban Legends in Education. Education Psychologist, 48:3, 169-183, DOI: 10.1080/00461520.2013.804395. See: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.804395

Lilienfeld, S., Lynn, S., Ruscio, J., Beyerstone, B., (2010). 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex, UK.

Marshik, Tesia, (2015). “Learning Styles and the Importance of Self-Reflection.” TEdxUWLaCrosse, Wisconsin. Published via YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=855Now8h5Rs

Moore, Cathy, 21 September 2010. “Learning Styles: Worth our Time?” See: http://blog.cathy-moore.com/2010/09/learning-styles-worth-our-time/

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). “Learning styles concepts and evidence.” Psychological science in the public interest, 9(3), 105-119. See: http://steinhardtapps.es.its.nyu.edu/create/courses/2174/reading/Pashler_et_al_PSPI_9_3.pdf

Pashler, H., and Rohrer, D., (2012). “Learning Styles: Where’s the Evidence?” Medical Education, 46, 630-635.

Stahl, S. (1999). “Different strokes for different folks? A critique of learning styles.” American Educator, 23(3), 27–31. (Cited in Kirschner)

The Debunker Club, “Learning Styles are NOT an Effective Guide for Learning Design.” Accessed 11 October 2016. See: http://www.debunker.club/learning-styles-are-not-an-effective-guide-for-learning-design.html

NAJSE Curriculum Designs were developed with a grant from the State Justice Institute (SJI-10-T-091) and published between 2011 and 2015. See https://nasje.org/nasje-curriculum-designs/

The author would like to thank NASJE colleagues Kelly Tait, Margaret Allen and Caroline Kirkpatrick for their assistance and support in the writing of this article.

Currently the Pima County Field Trainer, Nancy Smith has over 8 years of experience working in court training and education, first at the Washington State AOC and now at Pima County Superior Court (Tucson, AZ). She came to the courts with 16 years experience in education, both as a community college instructor and a high school teacher in Tucson, and as a curriculum coordinator at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA. Nancy teaches many kinds of court related classes, including soft skill topics like team building and time management, and court related topics like due process. She also does training and process analysis in computer applications. She speaks periodically at conferences on topics related to judicial education and publishes articles at NASJE.org. Currently, she serves on the NASJE Board as the Western Region Director. She earned her bachelor’s degree in French and History at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and her Master’s in French from the Free University of Brussels, Belgium. Nancy grew up in a Navy family, married into an Army family and served four years as an Army Intelligence officer. She has traveled widely around the United States and Europe as well as to Peru, Mexico and China. She likes the outdoors, and swims, hikes, bikes and does yoga to try and stay fit.

Currently the Pima County Field Trainer, Nancy Smith has over 8 years of experience working in court training and education, first at the Washington State AOC and now at Pima County Superior Court (Tucson, AZ). She came to the courts with 16 years experience in education, both as a community college instructor and a high school teacher in Tucson, and as a curriculum coordinator at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA. Nancy teaches many kinds of court related classes, including soft skill topics like team building and time management, and court related topics like due process. She also does training and process analysis in computer applications. She speaks periodically at conferences on topics related to judicial education and publishes articles at NASJE.org. Currently, she serves on the NASJE Board as the Western Region Director. She earned her bachelor’s degree in French and History at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and her Master’s in French from the Free University of Brussels, Belgium. Nancy grew up in a Navy family, married into an Army family and served four years as an Army Intelligence officer. She has traveled widely around the United States and Europe as well as to Peru, Mexico and China. She likes the outdoors, and swims, hikes, bikes and does yoga to try and stay fit. -

From the President (Fall 2016)

NASJE President Caroline Kirkpatrick To my NASJE colleagues,

Best wishes for a joyous holiday season, time with family and friends, good health and happiness.

If it’s possible, I encourage you to take a short break from thinking about judicial branch education and prepare to re-engage in 2017. Our organization is strong, our members are active and supportive of NASJE’s vision and strategic plan, and our valuable work continues.

Thank you for everything that you do for your state, your organization, your colleagues, your constituents and NASJE.

Caroline Kirkpatrick, President, NASJE