Committees: Where the Magic Happens

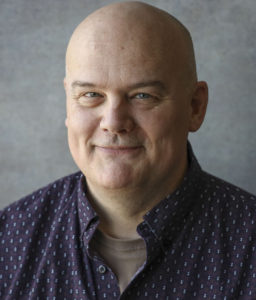

When I took office last year, I was asked repeatedly about my agenda as President of NASJE and what I hoped to accomplish. I struggled to provide an answer. My initial inclination was to say, “Continue the great work and follow the lead of the talented people who came before me.” My second reaction was even shorter and less impressive: “Try not to screw anything up.”

But the more I thought about it, the more an answer began to materialize. I wanted to work to ensure that NASJE would continue to be the resource to others that it has been to me. I asked myself what I had gotten out of NASJE, what were the most significant benefits I derived from being a part of the organization. Here is the list I developed.

- I acquired a greater understanding of how to be an effective judicial educator.

- I gained increased confidence in myself as a leader.

- I developed relationships with some of the most special people I have ever known.

Then I asked myself, “When and where did these extraordinary things happen?” Was it in one-on-one conversations with other NASJE members? In some ways the answer was yes, but not fully. Was it at the national conference? Again, to a degree, but not completely. Then it hit me. The place where the greatest number of important things happened for me was in the committees on which I served. Then-Professor and future president Woodrow Wilson once famously observed, “The real work of Congress is accomplished in committees.” With a nod toward Professor Wilson, I can honestly say that for me, “The real magic of NASJE takes place in the committees.”

Thus, my priority as I became president was to enhance and strengthen NASJE’s committee structure. There were impressive people I wanted to appoint to committees and others I hoped would serve in leadership positions. There were some vital committees that needed to be reminded about how truly essential they are. I believe I have accomplished these two objectives. My third goal was to find a way to increase the number of people participating in committees. I hope to take steps toward that objective in this piece.

I will be the first to admit, committees aren’t sexy. Not many people become a part of an organization, whispering in hushed and awed tones, “Ooh, I can’t wait to get involved with committees.” When imagining rewarding and exciting professional activities, one thinks of things like travel, presenting at national conferences or working on statewide initiatives. Not serving on committees.

However, it is in committees that NASJE members wrestle with the issues facing judicial educators. They explore problems. They exchange ideas. They develop solutions. They pick up pieces when things don’t go as planned and work to make it better. It’s not always pretty. It’s not always fun. But it puts you up to your elbows in matters of judicial education. And that is where you learn. You are probably thinking at this point, “Wow, you make it sound so glamorous. Where do I sign up? NOT!” I’m not going to sell you a bill of goods or push a false vision on you. It’s not always easy, but it is where things happen. It’s where you make a difference. Isn’t that what drew you to education in the first place?

In our recent survey of NASJE members, 31% of those who responded said that they joined our organization for leadership opportunities. Committees offer the initial opportunity for leadership. In fact, very few people end up on the Board of Directors who have not been leaders on our committees. It was on committees that I had the opportunity to watch people like Kelly Tait, Jeff Schrade, Caroline Kirkpatrick, and Lee Ann Barnhardt exercise a style of leadership that I learned from and sought to emulate. It was on the Education and Curriculum Committee that I was privileged to engage in leadership with Judith Anderson and Janice Calvi, two individuals with the hearts of angels, the courage of lions and the wisdom of Solomon.

Finally, committees are where I have forged some of my closest personal connections. The number is too vast for individual identification here (you know who you are). These people have consistently demonstrated commitment, insight and a capacity for problem-solving on a wide range of committees. As I worked beside these amazing individuals, I became close friends with them. These are people who changed my life. I want other members of NASJE to have this same experience. If you are just paying your dues and showing up to the occasional conference, you are not getting everything out of NASJE that you can.

I think some of us fall into the trap of thinking that everyone is fully aware of the committee structure in NASJE, when the reality is something quite different. Thus, I will conclude this message by reminding you of the opportunities to serve on NASJE committees. If you are interested, just let me know and I will make it happen.

The Communications Committee: This committee plays the essential role of facilitating communication among the members of NASJE. The committee is responsible for the NASJE website, developing news content as well as coordinating member contributions. In addition, the committee oversees the website’s resources, information and communications networks. The committee also takes a leading role in managing NASJE social media sites.

The Education and Curriculum Committee: At the heart of this committee is the ongoing conversation about how to improve judicial education and the quality of justice administered by our courts. This committee plans sessions to be presented at the annual conference, orchestrates webinars and callinars for NASJE members and oversees creation, maintenance and updating of the Curriculum Designs.

The Diversity, Fairness and Access Committee: This committee brings the issues of diversity, fairness and access to the forefront in a number of different venues, from planning and conducting educational sessions at the conference and throughout the year to bringing these important issues to the attention of the members of NASJE in the way we operate our organization and run our courts.

Membership and Mentor Committee: For an organization currently undergoing dramatic change, this committee serves the essential task of supporting members of NASJE and promoting the value of membership. This committee takes a leading role in identifying mentors and linking them with new members, an invaluable service in helping judicial educators to thrive.

The Futures Committee: This committee keeps NASJE focused on tomorrow. It is currently involved in implementing the existing strategic plan and will be at the heart of our next strategic plan. This group identifies trends in education, the law, society and technology and ways for NASJE to address a constantly changing world.

The Conference Planning Committee: As the name implies, this is the committee that plays a central role in making our conferences come together. From identifying the conference theme and setting the agenda to planning educational sessions and events, the members of this committee are an essential part of our outstanding conferences.

I welcome you to join us in making the magic of NASJE happen.

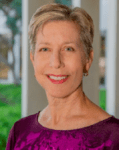

Formerly the Pima County (Arizona) Field Trainer and a Superior Court Training Coordinator, Nancy Smith has over 10 years of experience working in court training and education, first at the Washington State AOC and at Pima County Superior Court (Tucson, AZ). She currently is a partner at Sustainable Change Coaching and Consulting. She came to the courts with 16 years of experience in education, both as a community college instructor and a high school teacher in Tucson, and as a curriculum coordinator at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA. Nancy taught many kinds of court related classes, including topics such as implicit bias and faculty development, and court related topics like due process and procedural fairness. She has a special interest in adult learning theory and application. Nancy has branched out into a new business, where she and her partner plan to teach court leaders coaching skills to improve employee performance and retention. She speaks periodically at conferences on topics related to judicial education and publishes articles for the National Association of State Judicial Educators (NASJE). Currently, she serves on the NASJE Board as the Western Region Director as well as on the Communication and Conference Committees. She earned her bachelor’s degree in French and History at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and her Master’s in French from the Free University of Brussels, Belgium. Nancy grew up in a Navy family, married into an Army family and served four years as an Army Intelligence officer. She has traveled widely around the United States and Europe as well as to Peru, Mexico and China. She likes the outdoors, and swims, hikes, bikes and does yoga for fun and fitness. She can be reached at

Formerly the Pima County (Arizona) Field Trainer and a Superior Court Training Coordinator, Nancy Smith has over 10 years of experience working in court training and education, first at the Washington State AOC and at Pima County Superior Court (Tucson, AZ). She currently is a partner at Sustainable Change Coaching and Consulting. She came to the courts with 16 years of experience in education, both as a community college instructor and a high school teacher in Tucson, and as a curriculum coordinator at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA. Nancy taught many kinds of court related classes, including topics such as implicit bias and faculty development, and court related topics like due process and procedural fairness. She has a special interest in adult learning theory and application. Nancy has branched out into a new business, where she and her partner plan to teach court leaders coaching skills to improve employee performance and retention. She speaks periodically at conferences on topics related to judicial education and publishes articles for the National Association of State Judicial Educators (NASJE). Currently, she serves on the NASJE Board as the Western Region Director as well as on the Communication and Conference Committees. She earned her bachelor’s degree in French and History at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and her Master’s in French from the Free University of Brussels, Belgium. Nancy grew up in a Navy family, married into an Army family and served four years as an Army Intelligence officer. She has traveled widely around the United States and Europe as well as to Peru, Mexico and China. She likes the outdoors, and swims, hikes, bikes and does yoga for fun and fitness. She can be reached at  The National Association of State Judicial Educators is launching its Vision 2020 Campaign with a membership survey developed by the organization’s Membership and Mentor Committee.

The National Association of State Judicial Educators is launching its Vision 2020 Campaign with a membership survey developed by the organization’s Membership and Mentor Committee.